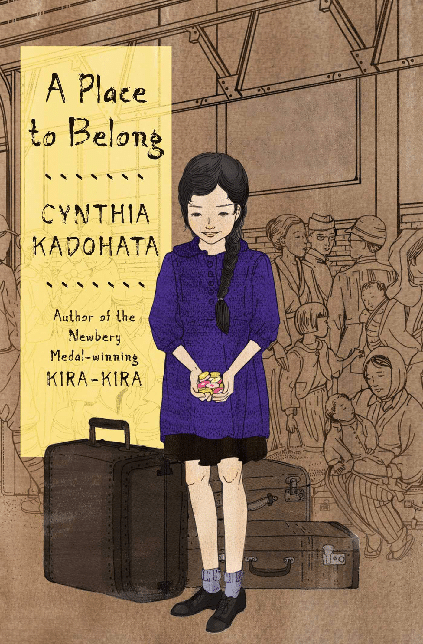

A Place to Belong

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: war, family, resilience, emigration, Hiroshima

A Japanese-American family, reeling from their ill treatment in the Japanese internment camps, gives up their American citizenship to move back to Hiroshima, unaware of the devastation wreaked by the atomic bomb in this piercing look at the aftermath of World War II by Newbery Medalist Cynthia Kadohata.

World War II has ended, but while America has won the war, twelve-year-old Hanako feels lost. To her, the world, and her world, seems irrevocably broken.

America, the only home she’s ever known, imprisoned then rejected her and her family—and thousands of other innocent Americans—because of their Japanese heritage, because Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Japan, the country they’ve been forced to move to, the country they hope will be the family’s saving grace, where they were supposed to start new and better lives, is in shambles because America dropped bombs of their own—one on Hiroshima unlike any other in history. And Hanako’s grandparents live in a small village just outside the ravaged city.

The country is starving, the black markets run rampant, and countless orphans beg for food on the streets, but how can Hanako help them when there is not even enough food for her own brother?

Hanako feels she could crack under the pressure, but just because something is broken doesn’t mean it can’t be fixed. Cracks can make room for gold, her grandfather explains when he tells her about the tradition of kintsukuroi—fixing broken objects with gold lacquer, making them stronger and more beautiful than ever. As she struggles to adjust to find her place in a new world, Hanako will find that the gold can come in many forms, and family may be hers.

In the opening pages of A Place to Belong, the author introduces the reader to Hanako (pronounced: HA-nah-koh) and her little brother Akira (pronounced: AH-key-rah) as they board a ship leaving the United States to sail to Japan. Hanako, Akira, and their parents had been living in Los Angeles on December 7, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked the U.S. fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor. Not long after, their family was incarcerated in Japanese relocation camps as enemies and potential saboteurs. During this period, Hanako’s parents renounced their American citizenship and with it their right to live in the United States. As a result, in 1945 the whole family is being deported to Japan.

Climbing aboard the ship and looking for their bunks, Akira says to his older sister, “Hanako, I’m afraid. Why do we have to go on this ship?”

“Because we don’t belong in America anymore,” she says as she dusts herself off.

“I think I do. I do belong in America,” Akira counters.

In this lengthy text written for middle school students, author Cynthia Kadohata tells the story of Hanako, Akira, and their parents as they leave the only home the children have known to go to Japan and live with their grandparents. They arrive to discover a nation overwhelmed by poverty and destruction. The children meet grandparents who love them dearly but have barely enough food to feed themselves. Communication between grandparents and grandchildren is conducted at first in stilted English, but eventually a powerful loving relationship develops between them. In the larger community, however, conditions are more complicated. Poor orphans view the Americans as rich outsiders and steal from them. New schoolmates tease Hanako and Akira because of their poor Japanese language skills and their American clothing. Before long, Hanako’s parents realize they made a big mistake by returning to Japan, and they seek the long-distance assistance of an American lawyer to help them recover their citizenship and return to the United States. Frustrated in their attempts, Hanako’s parents decide at the end of the story that if their children are to have any hope of succeeding in life, Hanako and Akira must return to California to live with their aunt, even if they will face racism. (Since they were both born in the United States they hold American citizenship.) The parents, meanwhile, will remain in Japan while they continue to fight for the same right to return. Hanako and Akira are excited to go back to the U.S. but heartbroken at leaving their parents and the grandparents they have grown to love. Throughout the book, the entire family struggles to find “a place to belong.”

While many American students are familiar with the Japanese relocation camps, the vast majority are unaware of the plight of those who returned to Japan. In 1944, Congress passed the Renunciation Act, which President Roosevelt quickly signed into law. By so doing, lawmakers hoped Japanese American internees would renounce their citizenship, thereby allowing immigration officials to deport them to Japan. In the end, 5,589 Japanese Americans officially renounced their citizenship, most coming from the Tule Lake Internment Camp (5,461) in California. While it is impossible to determine the motivations of each of these renunciants, the vast majority had been forcibly removed from their homes, stripped of their employment, incarcerated, and assumed to be a danger to society. It is no wonder so many felt they had no future in the United States and willingly renounced their citizenship. Others, such as Minoru Kiyota, renounced his citizenship “to express my fury toward the government of the United States” for his treatment during the war (Ngai, Impossible Subjects, pg. 192).

Following the war, U.S. attorney Wayne Collins filed a class-action lawsuit to allow all renunciants to reobtain U.S. citizenship. He argued that since their decision to return to Japan was made under duress, their citizenship should be restored. When the class-action suit failed, Collins proceeded to file individual affidavits on behalf of each affected individual. The first successful restoration of citizenship came in 1951. The last was in 1968.

Because these details are little known, A Place to Belong is a valuable resource in the classroom. Furthermore, it touches on themes relevant to students in the twenty-first century. Many students come from immigrant families with emotional and family ties in multiple countries, and many of them are increasingly fearful for their safety in American society. Some Americans clamor to build a wall to “protect” U.S. borders. Some decry the arrival of “kung flu.” Still others engage in acts of violence, as we have seen in the 2021 mass shooting targeting Asian Americans in Atlanta. According to a 2022 AAPI survey, nearly a third of Asian Americans report having experienced a hate crime during 2021 (http://aapidata.com/blog/year-after-atlanta/).

Today we celebrate the loyalty and self-sacrifice of many of these same Japanese Americans who were interned during the war. Approximately 30,000 volunteered to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces. The 442nd Infantry Regiment, which consisted almost entirely of Japanese Americans, became the most decorated unit in U.S. military history. Recognizing the bravery and loyalty of these Japanese Americans and admitting the government’s moral failings in unlawfully sending so many to relocation camps, in 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned. A Place to Belong reminds us of another group of Japanese Americans who made extremely difficult and brave choices as they left their adopted homeland and sought to start a new life in war-ravaged Japan.

Author: David Kenley, Dean of the College or Arts and Sciences, Dakota State University

2023

Appropriate Age/Grade Level

A Place to Belong is most appropriate for middle grades but could also be used with some upper elementary or younger high school students, depending on their reading level and interest (overall grades 6+).

Context

A number of young adult and middle-grade books about Japanese internment camps have been written from the perspective of Japanese Americans who endured and survived the experience during World War II. Two outstanding examples are Weedflower by Cynthia Kadohata and They Called Us Enemy by George Takei. A lesser-known piece of this story involves the 1944 Congressional passage of the Renunciation Act (Public Law 78-405), which encouraged people who had been interned during the war to renounce their American citizenship so that the U.S. government could deport them to Japan. A Place to Belong steps out of the United States to look at the 5,589 Japanese Americans who, following internment and the passage of the 1944 Renunciation Act, renounced their U.S. citizenship. Reasons for Japanese American renunciation varied from anger with the United States government over internment to hopelessness about their future in a country that had stripped them of their livelihood and limited their opportunities.

A Place to Belong begins with the deportation of twelve-year-old Hanako (pronounced: HA-nah-koh) and her family to Japan, where her father and mother grew up but where she and her brother, Akira (AH-key-rah), have never been. In the case of Hanako’s father, he does not see a future for his family in the United States, after the loss of their property and business and the humiliation of internment. Ultimately, they decide to join Hanako’s grandparents on a farm outside Hiroshima. There, the family set out to build a new life for themselves in a postwar world.

Common Core Standards

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.7: Conduct short research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question), drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions that allow for multiple avenues of exploration.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-10.9: Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis reflection, and research.

Literary Themes

Family, wartime (economics, laws), opportunity, displacement, citizenship, identity

Concepts and Entry Points

Each of the concepts that follow can be used to reinforce understanding, open discussion, or serve as a jumping-off point into a portion of the book or research connected to the novel.

1944 Renunciation Act (Public Law 78-405)

This congressional law leads to the deportation of Hanako and her family. Hanako’s family loses their American citizenship and moving to Japan to live with Hanako’s grandparents outside Hiroshima.

Hiroshima

With Hanako’s grandparents living outside of Hiroshima, the dark shadow of the nuclear bomb lingers at the edge of their world; her grandparents have been spared, but the book reveals that many who survived still have to fight for their lives.

Opportunity Cost

The novel provides many chances to talk about opportunity cost or the loss of potential gain when a different choice is made.

Hibakusha (pronounced: he-BAH-KU-shah)

This term refers to people who survived the atomic bombing. Hibakusha is not used in the text but could be used for additional research.

Postwar Japan

The novel gives a glimpse into the grim circumstances that the people of Japan faced after World War II ended.

Rice Farming

Rice is highly valued in Japanese culture. The war and the nuclear bombings led to a decrease in rice production.

U.S. Attorney Wayne Collins

This U.S. Attorney unsuccessfully filed a class-action lawsuit on behalf of Japanese Americans who renounced their citizenship; later, he filed individually for each person, winning cases between 1951 and 1968.

Guiding Questions

- What specific reasons do you think Hanako’s father had for renouncing his family’s citizenship? Provide specific examples from the text.

- What did Hanako learn about Hiroshima from her time in Japan? Give specific examples.

- What factors allowed Hanako’s grandparents to be better off than other people in Japan after World War II?

- What factors prevented Hanako’s family from achieving the success that they’d had in the United States?

- What circumstances led Hanako to return to the United States? Do you think that this was the right decision? Why or why not?

Suggested Learning Activity/Evaluation/Assessment

1. Have students agree or disagree about the tradeoffs of opportunity costs; use the examples below or ask students to fill in the statements with their own words. They could also create their own opportunity-cost statements.

-

- Renouncing American citizenship in exchange for [being part of the ethnic majority in Japan]

- Hanako sharing crackers with the boy from Hiroshima at the risk of [not having food for Akira]

- Hanako’s grandmother selling her wedding kimono in exchange for [the skirt that Hanako wanted]

- Hanako returning to the United States at the risk of [growing apart from her family]

2. Have students research specific Wayne Collins cases, in which he advocated for famous Japanese Americans: Abo v. Clark (1946), Koramatsu v. United States, and Iva Ikuko Toguri D’Aquino [aka “Tokyo Rose”] v. United States

3. Have students work in groups of two to three and analyze the images in this photo essay from The Atlantic, “Japan in the 1950’s.”[1] Students should respond to the following three As, followed by a turn-and-talk, then large class discussion:

-

- Affirm: What does this affirm that you read/learned about in A Place to Belong?

- Ask: What questions would help you make better sense of this image?

- Argue: What information makes you question what is being presented in this image?

Possible Resources

- “Documents, Court Documents for Tadayasu Abo et. Al vs. William P. Rogers, San Francisco in California, 03/10/1958.” | National Museum of American History. Accessed December 31, 2023. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/nmah_1800502.

- Dower, John W. “Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors.” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2008. https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/groundzero1945/gz_essay04.html.

- Kadohata, Cynthia. Weedflower. New York: Aladdin Paperbacks, 2009.

- Takei, George, Justin Eisinger, Steven D. Scott, and Harmony Becker. They Called Us Enemy. San Diego, CA: Top Shelf Productions, 2020.

- Takei, George. “Wayne Collins.” Remembrance Project – Wayne Collins, 2012. http://remembrance-project.janm.org/tributes/wayne-collins.html.

- Taylor, Alan. “Japan in the 1950s.” The Atlantic, March 12, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2014/03/japan-in-the-1950s/100697/.

- Wojtan, Linda S. “Rice: It’s More Than Food in Japan.” FSI, 1993. https://spice.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/rice_its_more_than_food_in_japan.

Author: Michael-Ann Cerniglia, Upper School History Teacher, Winchester Thurston,

2023

[1] Alan Taylor, “Japan in the 1950s,” The Atlantic, March 12, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2014/03/japan-in-the-1950s/100697/.