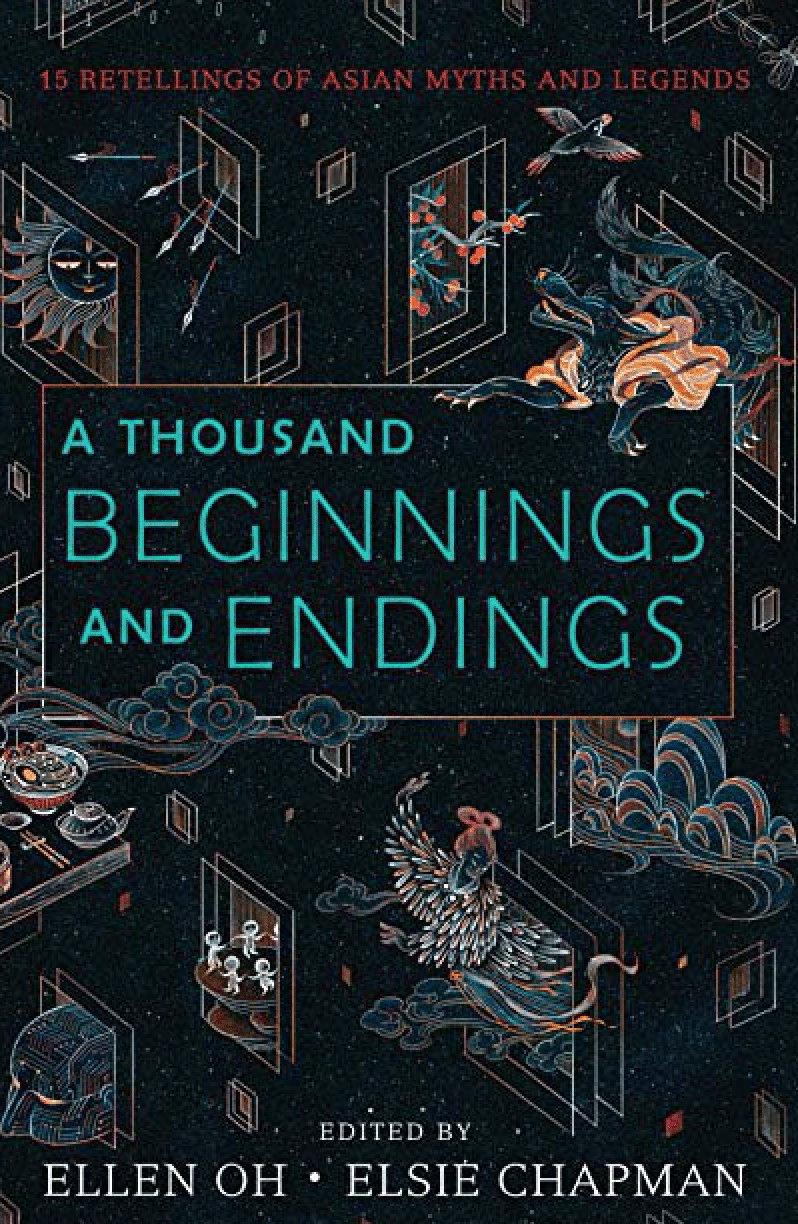

A Thousand Beginnings and Endings

- Fiction

- Set in East and South Asia

Keywords: fantasy, sci-fi, romance, LGBTQIA

Star-crossed lovers, meddling immortals, feigned identities, battles of wits, and dire warnings: these are the stuff of fairy tale, myth, and folklore that have drawn us in for centuries. Fifteen bestselling and acclaimed authors reimagine the folklore and mythology of East and South Asia in short stories that are by turns enchanting, heartbreaking, romantic, and passionate.

Compiled by We Need Diverse Books’s Ellen Oh and Elsie Chapman, the authors included in this exquisite collection are: Renée Ahdieh, Sona Charaipotra, Preeti Chhibber, Roshani Chokshi, Aliette de Bodard, Melissa de la Cruz, Julie Kagawa, Rahul Kanakia, Lori M. Lee, E. C. Myers, Cindy Pon, Aisha Saeed, Shveta Thakrar, and Alyssa Wong.

A mountain loses her heart. Two sisters transform into birds to escape captivity. A young man learns the true meaning of sacrifice. A young woman takes up her mother’s mantle and leads the dead to their final resting place. From fantasy to science fiction to contemporary, from romance to tales of revenge, these stories will beguile readers from start to finish.

Overview:

A Thousand Beginnings and Endings is an anthology of sixteen short stories, reinterpretations of folk tales, myths, and religious texts from China, India, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, and more. Edited by Ellen Oh and Elise Chapman, this collection includes everything “from fantasy to science fiction to contemporary, from romance to tales of revenge” (HarperCollins Publishers), allowing young adults to encounter Asian culture through the relatable, inviting eyes of teen narrators who are often modern Westerners of Asian descent.

Select Common Core Standards:

RL.9-10.9: Analyze how an author draws on and transforms source material.

W.9-10.3: Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

W.9-10.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

SS.9-10.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary describing political, social, or economic aspects of history.

SS.9-10.7: Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event.

Appropriate Student Population:

While most of the stories would hold the attention of an adult, the anthology’s themes and accessible writing make it most suitable for students at the 7th–10th grade levels. Their length—each is less than 30 pages—coupled with the variety of cultures represented make these stories easy to insert into existing units in a Literature/English classroom, or to include in a cross-disciplinary collaboration between English and Social Studies or Japanese/Mandarin. If cross-curricular collaborations aren’t possible, I would only recommend using A Thousand Beginnings in Social Studies or Language classes as enrichment, since these stories are modern reinterpretations largely told by Western narrators and lack historical or geographic context. A couple other warnings:

- Kanakia’s “Spear Carrier” has language that comes across as extreme in an anthology that is otherwise quite tame.

- There are allusions to sexual intercourse. Only Pon’s and Kagawa’s stories contain slightly more graphic details.

- The anthology seldom includes non-English vocabulary, and many stories have been Westernized. This makes the reading easier, but culturally watered-down.

Entry Points and Suggestions for Social Studies and English Classrooms:

Because most stories lack historical or geographic context, A Thousand Beginnings offers few opportunities to reinforce or assess content commonly taught in World History or Geography classrooms:

- The American West and Yu Lan (Hungry Ghost) Festival – Wong’s “Olivia’s Table” centers on a Chinese American teen who is tasked with cooking for the deceased during a former Gold Rush town’s Hungry Ghost Festival, the author’s reinterpretation of the Chinese Yu Lan Festival. Most of the ghosts the character encounters are Chinese who contributed to building the modern American West, railroad workers in particular.

- Hindu epics and holidays – Chhibbar’s “Girls Who Twirl” takes place during a Navratri celebration and includes multiple passages from Vedic texts. Navratri, a Hindu festival dedicated to the Hindu goddess Durga, is celebrated through community dances, which are featured in the story. A Thousand Beginnings also includes two stories derived from the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic foundational to Hinduism. Kanakia’s story deals with the “Bhagavad Gita” book of the Mahabharata, which focuses on answering the question: What’s the point of life? Thakrar’s story looks at the “Savitir and Satyavan” tale in the Mahabharata, which describes a wife’s love and courage in the face of her husband’s impending death.

- Japanese feudalism – Kagawa’s “Eyes like Candlelight” is set in premodern Japan. The terms shogun, daimyo, and samurai are used and because much of the story is focused around whether or not a small village will be able to pay the daimyo’s rice tax, we get an example of how these positions operated in Japan prior to 1868.

- Female court officials – Bodard’s “The Girl with the Vermillion Beads” tells the story of young sisters working in the emperor’s imperial palace as census accountants. The practice of using women for census-taking tasks was not specific to feudal Vietnam, also existing in China and Japan, and was an avenue for female advancement in highly patriarchal societies.

Given the anthology’s deliberate focus on expressing universal human themes through regionally specific myths, A Thousand Beginnings is better geared to an English Literature classroom. The main themes are listed below. Each figures strongly in at least a third of the tales.

- The supernatural – Since A Thousand Beginnings is an anthology of legends and folk tales, the supernatural is present in all the stories. Deities, ghosts, goblins, vampires: cultures around the world have their own versions of these things, which could stimulate interesting discussions.

- Female voices — At least twelve of the sixteen stories are reinterpretations designed to depart from the original folk tales by either including a female narrator or centering on female characters. Bodard, for instance, features two supportive sisters in her retelling instead of the competitive siblings in the traditional tale. Few of the stories deal with racial issues or sexual identity, the exceptions being Wong’s “Olivia’s Table” and de la Cruz’s “Code of Honor.”

- (Forbidden/uncommon) romantic love – This occurs almost always between humans and deities/spirits. The works by Chokshi, Thakar, Pon, and Kagawa are the best examples. These stories might be a good way to draw comparisons to similar tales in Western mythologies.

- Feeling trapped or misunderstood, and the desire for independence – This is a common YA book theme, and it can be found in at least half the stories. Bodard, Saeed, and Thakrar describe young females literally trapped in palaces. Meyer’s creatively involves a girl who gets transported and stuck in a World of Warcraft–style videogame. Oh’s story focuses on a demanding mother. De la Cruz’s is about a forever sixteen-year-old vampire trying to hide her identity.

- Grief – Grief over the loss of a loved one, particularly parents and lovers, is a recurring theme. Stories by Wong, Lee, Meyers, and de la Cruz are all focused on dealing with the death of a mother. Tales by Chokshi, Charaipotra, Thankrar, and Kagawa include the death of a lover.

Other Suggested Learning Activities:

- Compare Western and Asian ideas about the occult (goblins, vampires, etc.). Do the same with Western and Asian mythologies.

- Use one or more of these stories during the Halloween season to keep things “festive” while providing students with a global context.

- Have students reinterpret the stories (or source texts) into short role plays or cartoon strips.

- Ask: What is a legend from your faith/cultural tradition? Encourage students to reinterpret. Ask: How does this story reflect your family’s culture and ancestry?

- Compare any of the tales to the primary source material. Ask: What did the author alter? What remained the same? Why? I could see reading the original story first and using the retelling in A Thousand Beginnings as a high-level extension/assessment of comprehension.

- Watch (or better yet, try to learn steps from) the Garba, Dandiya Raas, or Ras Garba—three dances commonly done during the Hindu festival of Navratri (in Chhibber’s story).

- Have a Yu Lan celebration or research and make recipes associated with Yu Lan.

- If your school is lucky enough to have a Mandarin or Japanese program, the stories taking inspiration from China (Wong, Chapman, Pon) and Japan (Kagawa) could be opportunities for a quick humanities-languages partnership.

Author: Matthew David Williams, Social Studies Teacher, Oakland Catholic High School, 2024