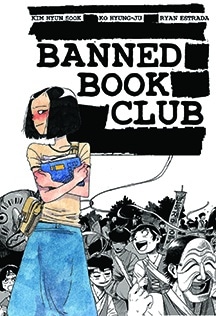

Banned Book Club

- Non-fiction

- Set in Korea

Keywords: graphic novel, politics, human rights, activism, friendship

When Kim Hyun Sook started college in 1983 she was ready for her world to open up. After acing her exams and sort-of convincing her traditional mother that it was a good idea for a woman to go to college, she looked forward to soaking up the ideas of Western Literature far from the drudgery she was promised at her family’s restaurant. But literature class would prove to be just the start of a massive turning point, still focused on reading but with life-or-death stakes she never could have imagined.

This was during South Korea’s Fifth Republic, a military regime that entrenched its power through censorship, torture, and the murder of protesters. In this charged political climate, with Molotov cocktails flying and fellow students disappearing for hours and returning with bruises, Hyun Sook sought refuge in the comfort of books. When the handsome young editor of the school newspaper invited her to his reading group, she expected to pop into the cafeteria to talk about Moby Dick, Hamlet, and The Scarlet Letter. Instead she found herself hiding in a basement as the youngest member of an underground banned book club. And as Hyun Sook soon discovered, in a totalitarian regime, the delights of discovering great works of illicit literature are quickly overshadowed by fear and violence as the walls close in.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once famously said: “Censorship reflects a society’s lack of confidence in itself. It is a hallmark of an authoritarian regime.” This remark has special significance for South Korea, as illustrated in Banned Book Club, a graphic novel by Kim Hyun Sook (pronounced KIM hyuhn-suk).[1]With vivid personal memories deftly woven into the tapestry of national history, this book offers a new understanding of South Korea’s arduous journey toward democracy in the 1980s. These Culture Notes offer some historical background.

The Burim Case

“April is the cruelest month,” begins The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot’s lament for Western civilization after WWI. In the 1980s South Korea, this line became a pervasive trope for the nation’s history laden with a multitude of traumatic events that had occurred in the spring. Banned Book Club is telling of the special resonance the trope had with young people in South Korea under the military regime, who like Hyun Sook, entered university full of curiosity and hopes, only to see their fervor for learning repeatedly dashed by state censorship.

During freshmen orientation, new students are cautioned against participating in anti-state activities, with the Burim incident held up as a warning. The Burim incident refers to the arrests in 1981 of twenty-two teachers, college students, and office workers on the charge of forming a book club to read what was considered seditious literature.

They were detained without due process for almost two months, during which the police tortured them to extract false confessions and incriminate them as supporters of North Korea. Eventually, nineteen were convicted of breaking the National Security Law and sentenced to prison terms ranging from one to seven years. That verdict was upheld by South Korea’s Supreme Court in 1983 (Song 2014). (They were finally acquitted in 2014, 33 years later.)

A prime example of the despotic state’s ruthlessness in suppressing civil society and freedom of expression, the Burim incident has repeatedly surfaced in public discourse. The film The Attorney (Yang Woo-suk, 2013), a courtroom drama, recounts the efforts of former President Roh Moo-hyun (pronounced: NO my-hyuhn) to help the accused in the Burim trial as their defense attorney.[2] In a climatic courtroom scene, Attorney Song, based on Roh’s story, exposes the absurdity of the case by arguing that if books like What Is History by British diplomat and historian E. H. Carr are to be banned as seditious literature, the same logic should be applied to the people and institutes that recommended them, including the British embassy and Seoul National University, the alma mater of the judge and the prosecutor. Following this logic, virtually no one would be immune from accusations of violating the National Security Law.

Attorney Song’s impassioned speech resonates deeply with Hyun Sook’s firsthand experiences as a university freshman. When invited to a book club, she brings The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne and is stunned to discover that this classic is among the banned books in the Burim case. Her disillusionment does not end there, as she later learns that Jack London’s The Iron Heel are also banned, while his other works are freely circulated. In the springtime of her life, Hyun Sook sees South Korea as little more than Eliot’s Waste Land; the spring rain stirs dull roots, yet the possibility of any actual growth feels elusive. Then again, her unyielding spirit of resistance against censorship brings to mind Joseph Brodsky’s avowal that a crime worse than burning books is failing to read them.

The Origins of Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism emerged after Korea’s liberation in 1945 from Japan’s colonial rule. Instead of celebrating their independence, the Korean people witnessed the division of their nation when the U.S.–Soviet joint trusteeship was imposed, contrary to their collective desire for a unified nation-state. As the rivalry between the two global superpowers escalated, Korea was driven deeper into the maelstrom of Cold War paranoia. In the South, the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK) chose Syngman Rhee, a right-wing jingoist with strong ties to Washington, over other eminent national leaders, ostensibly for his promise to deliver swift stabilization of the political situation. This helped him to quickly solidify his political base through coalitions with conservative groups, including former Japanese collaborators,[3] and to establish autocratic power over the entire society.

Distrust of Rhee and the USAMGIK grew, which in turn led to the frequent use of the military and police to suppress dissident voices in society. In essence, the foundation of the first modern nation-state in South Korea did not rest on the people’s support, but rather on foreign interests and the repression of civil society (Choi 1993). Although a system of democratic governance was introduced, it did not hold much power. Korea is on a peninsula, situated between two major powers—China and Japan—and from its earliest history it has been shaped by outside forces.

The Korean War (1950–1953) deepened the rift between the repressive state and the powerless society, as it transformed South Korea from an unstable anti-communist state into an overdeveloped despotic one, complete with formidable censorship and policing apparatuses (Choi 1993). Cold War paranoia took root more deeply in South Korea during and after the war, serving as a magic wand for the autocratic state to maintain an iron grip on civil society. Simply, the war made South Korean society more congenial to the rise of authoritarianism. For almost forty years, the deep divide between the despotic state and the people continued, with the military dominating the government until the establishment of the first civilian government in 1993. It is not surprising, then, that during that period South Korea suffered a series of violent and tragic confrontations between the state and civil society, including the Jeju Uprising in 1948, the April 19 Revolution in 1960, the Gwangju Massacre in 1980, and the June Uprising in 1987.

The Gwangju Massacre

The Gwangju Massacre (also written Kwangju; pronounced: gwahng-jew) deserves special attention here, as Banned Book Club is set in the post-Gwangju era and has a chapter devoted to the event. In May 1980, the military regime’s brutal suppression of the pro-democracy uprising in the southern city of Gwangju resulted in massive civilian casualties and left South Korean society deeply traumatized.

The first military regime lasted for nearly two decades (1961–1979) under Park Chung-Hee (pronounced: PAHK juhng-he) and ended with Park’s assassination. Hope for a new era began to emerge but was soon extinguished when another military coup occurred, this one spearheaded by General Chun Doo-hwan (pronounced: CHUN do-han). South Korean society, weary after decades of authoritarian rule, mounted a staunch resistance against the rise of yet another military regime. Pro-democracy demonstrations spread across the nation. In a bid to quell the rising dissent and prevent the protests from escalating, the coup leaders singled out Gwangju as a target. They deployed paratroopers to the city and, as tensions escalated, ordered soldiers to open fire on demonstrators. The city was cut off from the rest of the nation, with all roads blocked, transportation halted, and telecommunications entirely disabled. The South Korean media were tightly controlled, repeating only what the government authorities dictated. The rest of the country remained largely uninformed or misinformed about the tragedy unfolding in Gwangju. Many believed what they were told: that the incident had been incited by North Korean spies and sympathizers.

The 1980 Gwangju Massacre continues to cast a long shadow over South Korean society due both to the military regime’s sheer cruelty and to a sense of guilt stemming from Gwangju’s isolation as it was brutalized by the fascist regime. Gwangju has also become a symbol of the indomitable spirit of resistance against unjust violence. The

Gwangju Massacre played a pivotal role in catalyzing the democracy movement through the 1980s. As state censorship tightened its grip, demands to remember Gwangju intensified, particularly among college students. As vividly depicted in Banned Book Club, the secret screening of Gwangju videos—compiled from raw footage captured by foreign journalists who managed to sneak in and out of Gwangju under siege—became a central element of the annual May demonstrations on South Korean college campuses in the 1980s.[4]

The Minjung Movement: Talchum (Mask Dance Drama) and Minjung Culture

South Koreans often refer to the democracy movement as the minjung movement. The word minjungtranslates to “people” in English. In the South Korean context, however, it carries profound historical and political significance, denoting the oppressed, in contrast to the ruling classes. At its core, the minjungdiscourse sought to empower the oppressed to reclaim their historical agency, identifying the minjung as the true protagonists of national history. Also, because they have long been subjected to injustice, they are in a position to expose fundamental flaws in the existing order and bring about real change, ultimately becoming the rightful owners of a democratic society. If authoritarianism had thrived on weak civil society, the minjungmovement emerged as a major catalyst for regenerating society. Thus, scholars like Lee Namhee went so far as to define it as “the most significant contributing factor in the ‘revival’ of civil society in South Korea” (2007, 10).

As the democracy movement gained momentum through the 1980s, the minjung discourse flourished and spread into various fields: historiography, philosophy, sociology, theology, literature, theatre, music, cinema, and more. The term minjung served as a powerful concept, especially for practitioners seeking to create a popular culture that reflects the concerns of the oppressed. Practitioners committed themselves to reviving lost folk culture traditions and returning them to their true owners, the minjung (Choi 1995). One notable example is the rediscovery of talchum (mask dance drama; prounounced: tahl-chum). Typically, talchum involves masked performers and a group of musicians who combine songs, dances, and dialogue into a dramatic performance. Talchum is renowned for over-the-top characters, satirical humor, and vulgar language used to ridicule the ruling classes and challenge hierarchies. It is also worth noting that talchum does not require a formal stage. Any open space can be used as a venue, making itaccessible to a broader audience. Furthermore, talchum performance is not rigidly scripted, but flexible and open, fostering lively interaction with the audience. Indeed, the audience plays an integral part in a talchumperformance, repeatedly invited to participate with their own cheers and jeers and often through direct spontaneous involvement in the performance. In brief, talchum is a manifestation of the minjung’s critical and creative energies in confrontation with ruling groups and cultures (Choi 1995).

As a major source of inspiration for the minjung culture movement, talchum became an important element in the cultural landscape of the 1970s and 1980s, particularly within youth and university culture. Talchum performance was often integrated into political rallies to inspire participants with the spirit of resistance. For minjung culture practitioners, the relationship between art and politics was intricate. To be sure, art is not politics. Yet it could never be divorced from politics, especially in the realm of folk arts. It is only through rigorous engagement with the realities of the oppressed and their arduous quest for justice that genuine minjung art can be created. This intricate interplay of art and politics is succinctly addressed in Banned Book Club, particularly in the talchum scene where Hyun Sook grapples with talchum’s political dimensions. She initially joined the talchum club to stay out of politics. After seeing a protest following her team’s performance, however, she realizes that talchum served as a prelude to the protest. This revelation leads her to ponder the relationship between art and politics, specifically within the minjung movement. In response to her inquiry, Hoon, a senior in her mask dance team, says, “In times like this, no act is apolitical.” He adds, “Your loud drumming is enough to get them [protesters] riled up for that [political action],” suggesting that the minjungmusic she created with her drum, consciously or not, was powerful enough to kindle the spirit of resistance in the protesters.

Incomplete Democratization and the Candlelight Protest

Banned Book Club concludes with a class reunion in 2016, which may strike some readers as a little odd. The novel leaves the reader without any definitive closure to all the intense struggles for democracy that Hyun Sook and her friends fought in the 1980s. A closer look reveals that this ending is deliberately framed to challenge the reader with some thought-provoking final questions that resonate with anyone interested in the ongoing democracy movement in South Korea today.

The class reunion is set amid the 2016–2017 Candlelight Revolution, which began in October 2016 as the nation was rocked by the corruption scandal surrounding President Park Guen-hye (pronounced: PAHK gu-nae) Park had allowed her confidant Choi Soon-sil—cult leader Choi Tae-min’s daughter, who had no government rank or status—to wield significant influence over state affairs. The investigation later revealed that Park and Choi had also engaged in extorting bribes from corporations, which were then funneled to Choi’s family and her nonprofit organizations. These shocking revelations triggered a wave of protests demanding Park’s impeachment. The Saturday-night vigils persisted throughout the winter to March 2017, drawing over 16 million participants from a population of 51 million. Ultimately, Park was impeached, removed from office, and sentenced to twenty-four years in prison; Choi, also convicted, received a twenty-year prison term.

The Candlelight Revolution reaffirmed the power of the people, but it left South Koreans with a host of questions. After all the arduous fights and noble sacrifices, what real change has the minjung movement truly achieved? Why does it often feel that society has remained largely unchanged? Is it only superficial change that has occurred, without genuine transformation? Why are we still out in the streets protesting three decades later? But as doubts and cynicism creep in and threaten to overshadow any hope for democracy, Hyun Sook offers a reassuring perspective: things get better, even when change feels frustratingly slow. Hoon adds a cautionary reminder: “Progress is not a straight line. Never take it for granted.” Banned Book Club ends with the important message that democratization is never complete, and in the ongoing fight for democracy, there can be no break.

The Manhwa (Comic Books) Culture

In the 2022 South Korean Netflix series Twenty-Five Twenty-One, the teenage protagonist Na Hee-do captivates viewers with her endearing obsession with manhwa (pronounced: mahn-hwa). She suffers many dilemmas as her mother rebukes her for her passion for fencing. Her mother scolds her for going to a club instead of studying, and criticizes Hee-do’s favorite manhwa series, Full House (1993–1999) by Won Soo-yeon (Park 2021). In a fit of rage, she retorts that her mother was never there during times of her heartbreak, and she found solace in Full House. Her mother’s disapproval of Hee-do’s love of manhwa sheds light on the unique place it holds in South Korea’s cultural landscape.

Manhwa, similar to manga in Japan and manhua in China, is the general term for comics and cartoons in South Korea. Despite a dearth of serious critical attention, manhwa has played a significant role in the shaping of South Korea’s popular culture, particularly among young people, including university students, as exemplified in Twenty-Five Twenty-One. It has served as an important outlet for the counter-cultural sensibilities of Korean youth. This cultural aspect reflects how manhwa are consumed. They are usually read during breaks in people’s daily lives. The manhwa bang (room), where one can read and borrow manhwa, is often discreetly tucked away between major buildings or in back alleys in bustling urban areas. In brief, it occupies an interstitial space amid the urban hustle and bustle, both physically and psychologically, and serves as a retreat or sanctuary from the highly coordinated and fast-paced Korean society.

Given the distinctive geo-psychological elements of manhwa culture, the choice to use this genre to deal with the weighty subject of the democracy movement in South Korea is intriguing. While this graphic novel may not appeal to historians or scholars, its use of manhwa as a storytelling tool will enchant readers and inspire them to engage in genuine reflection on serious questions.

Notes

[1] Korean names follow the Korean order, where the surname precedes the given name. The McCune-Reischauer system, the standard romanization system for Korean, is used here except for names and terms that are already well known to English readers, such as Kim Hyun Sook and Burim.

[2] After the Burim case, Roh worked as a human rights lawyer, helping democracy activists, before entering politics in 1988. Later, he served as President of South Korea from 2003 to 2008.

[3] Korea was a colony of Japan from 1910 to 1945.

[4] A scene of the Gwangju video screening on campus can also be found in a recent historical drama 1987: When the Day Comes(Jang Joon-hwan 2017).

References

Choi, Chungmoo. 1995. “The Minjung Culture Movement and the Construction of Popular Culture in Korea.” In South Korea’s Minjung Movement: The Culture and Politics of Dissidence, edited by Kenneth M. Wells, 105–118. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Choi, Jang-Jip. 1993. “Political Cleavages in South Korea.” In Hagen Koo, ed. State and Society in Contemporary Korea, 13-50. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Lee, Namhee. 2007. The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Park, Ji-won. 2021. “Comic Artist Won Soo-yeon Talks about Reprint of Full House Manhwa.” The Korea Times, May 18 (https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/culture/2023/09/135_309034.html).

Song, Bong-guen. 2014. “Five ‘Burim’ Defendants Acquitted 30 Years Later.” Korea JoongAng Daily, February 13 (https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2014/02/13/socialAffairs/Five-Burim-defendants-acquitted-33-years-later/2984946.html).

Author: Seung-hwan Shin, Teaching Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh

2023

Story Background:

The Banned Book Club recounts the experience of Kim Hyun Sook (pronounced: KIM hyuhn-suh), living under the military dictatorship in South Korea during the 1980s. This work of nonfiction is written in the style of manhwa (pronounced: mahn-hwa), South Korean comics (similar to Japanese manga). The book begins in 1983 when Hyun Sook is a first-year college student. She’s been preparing for this day for some time, working long hours in her family’s restaurant to save money for tuition, fighting with her mother, who is more traditional, about even attending college. She arrives on campus to find students protesting against the oppressive military regime that ruled South Korea throughout much of the 1980s. As the story continues, Hyun Sook highlights the precious value in examining art and literature, especially from Europe and the United States, as a means of enlightening political viewpoints. Hyun Sook joins a group that meets in secret to read and discuss banned books, many of which explore ideas about systems of government that are far different from the regime they are living under. Through these books and clandestine meetings, the students begin to form their own ideas about the future of the country they will inherit. The book club inspires the students to activism and helps solidify their role in ultimately toppling the military regime in favor of democracy in 1987. The book concludes with a flash forward to 2016, where we find Hyun Sook and her former classmates at a reunion. The reunion takes place at a protest against President Park Geun-hye (pronounced: PAHK goo-neigh) and not only illustrates the legacy of activism and protest that has continued in South Korea but also highlights the importance of finding community and support among fellow activists, as Hyun Sook did during her university years.

Political Background

The Banned Book Club is a graphic novel about the military dictatorship in South Korea during the 1980s. After the Korean War, South Korea experienced a tumultuous period of student uprisings and unstable leadership until the election of Park Chung-hee (pronounced: PAHK juhng-he) in 1963. Park ruled during the Third and Fourth Republics; his leadership style was socially and politically repressive with some progress in economic growth. Park was assassinated in 1979, ultimately leading to a military dictatorship. Under this Fifth Republic, President Chun Doo-hwan (pronounced: CHUN do-whan) systematically oppressed any political opponents and restricted free speech. It is during this period that The Banned Book Club begins.

Notably, the author starts her story after the 1980 Gwangju Uprising (pronounced: gwahn-jew), a series of student-led demonstrations demanding free and open elections. Ultimately, President Chun instituted martial law to stop these protests; many student leaders were arrested, and anyone present near the protest sites was in danger of being beaten by soldiers ordered to clear the area. It is with this alarming experience that Hyun Sook enters the university. The memoir covers several possible discussion topics related to Korean culture: class disparities, political activism, and art as politics.

Class Disparities

Kim Hyun Sook is not a typical university student; she comes from a working-class family that sometimes struggles to see the value in a post-secondary education. Hyun Sook does not have much support from her mother, in particular. The Kim family owns a steak restaurant, and Hyun Sook’s mother sees little to be gained in engaging with a university where students are protesting rather than studying; by contrast, she has worked hard to provide for her family with little education. This divide puts Hyun Sook in an awkward position between wanting to remain loyal to her family and seeking new opportunities. The second chapter, “Masked Folk Dance Team,” further illustrates the class divide Hyun Sook experiences. She performs with her new dance team at the university, in a show that reflects the historical distance between the educated class known as the yangban (pronounced: yahng-bahn) and the majority of Koreans. The yangban in the show are devoured by a monster representing the working class.

Similarly, Hyun Sook finds herself straddling the line between life at the university and her working-class family. This theme is revisited in the final chapter, “Class Reunion,” when Hyun Sook reunites with her university friends thirty-five years later, only to join a protest against then-president Park Geun-hye—the daughter of former president and dictator Park Chun-hee and a descendant of yangban. It seems that those who see themselves as elite or destined to rule Korea are still quite distant from the interests and needs of the Korean people.

Political Activism

At its heart, The Banned Book Club is a love letter to the student activists of the 1980s. Hyun Sook’s stories weave sentiments of the Gwangju Uprising into her own experiences with the banned book club she joins; students are portrayed as passionately devoted to their country. As various friends from the book club are targeted by police and interrogated, inspiration from books such as The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Motorcycle Diaries by Che Guevara, and The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan inspire the students to keep going despite their powerlessness in the face of authority. In the final chapter, the reunion of banned book club members concludes with a conversation in which Hyun Sook states, “People [must be] stubborn enough to fight for what’s right, even when no one’s listening…look for the truth, figure out what [you] believe, and stand up for it…[you] are not alone” (pg. 195). Political activism and the power of democratic ideals are essential to the university students’ experience in the 1980s and seem to have a lasting impact on political engagement in Korea as illustrated by the protests and subsequent impeachment of President Park Geun-hye in 2016.

Art as Politics

As the title suggests, The Banned Book Club places great value on the influence and impact of works of both fiction and non-fiction. The university students are forbidden from reading unapproved books, yet the banned book club acquires and reads such books despite the danger in being caught discussing ideas and actions against the government. At various points in the memoir, Hyun Sook refers to the impossibility of separating politics from the content of books or other art forms (“In times like this, no act is apolitical,” pg. 23). Throughout the memoir, Hyun Sook describes books (and eventually music, newspapers, and films) that she and her friends access illegally. In each resource, the group gains insights into political systems that the government has desperately tried to keep from its citizens.

Connections to Today

The book lends itself to contemporary issues such as public protest, democratic ideals, and student action. The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 or the March for Our Lives demonstrations in 2022 provide excellent parallels to Hyun Sook’s story. Students can discuss the role of art as political activism in these contemporary movements as well as in Hyun Sook’s experiences. Likewise, the concept of free speech is relevant to the battles currently being fought in public schools and libraries across America (see https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10). What is the role that governmental figures play in regulating the information accessed by its citizens? What information should citizens be able to access? Presented alongside current events, this book could elicit valuable classroom discussions and debate.

Curriculum Connections

The Banned Book Club would be an excellent book or resource in the secondary classroom. Due to some violence and complex political themes, grades 7–12 would be most appropriate. Standards with connections to themes in The Banned Book Club include the following:

NCSS Standards:

Culture & Society: In a democratic and culturally diverse society, students will comprehend multiple perspectives that emerge from within their own culture and from the vantage points of the diverse cultural groups within that society.

Civic Ideals & Practices: Students will explore how individuals and institutions interact. They will also seek to understand different points of view and weigh the evidence used to support various perspectives. Students learn through active learning experience how to participate in community service and political activities and how to use democratic processes to influence public policy.

Common Core, ELA grades 7–12:

RI.11-12.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze how an author uses and refines the meaning of a key term or terms over the course of a text (for example, how Madison defines faction in Federalist No. 10).

RI11-12.7: Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats (visually, quantitatively, etc.) as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

Recommended Resources

English Language Arts Standards, Reading: Informational Text, Grade 11–12.” Common Core State Standards Initiative. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.marylandpublicschools.org/programs/Documents/ELA/Standards/Grades_9-12_MCCR_Standards.pdf

“National Curriculum Standards for Social Studies: Introduction.” Social Studies. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.socialstudies.org/standards/national-curriculum-standards-social-studies-introduction.

Oberdorfer, Don, and Robert Carlin. The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

Additional Pronunciation Notes

Family names are given first in this essay: Kim, Park

Kim = pronounced like the English name Kim

Hyun = barely pronounce the “h” and slide immediately to the “yuhn”

Sook = the “oo” is pronounced like “u” in “put” and the “k” is silent

Author: Stephanie Rizas, IB History of Asia teacher, Bethesda–Chevy Chase High School, Maryland

2022