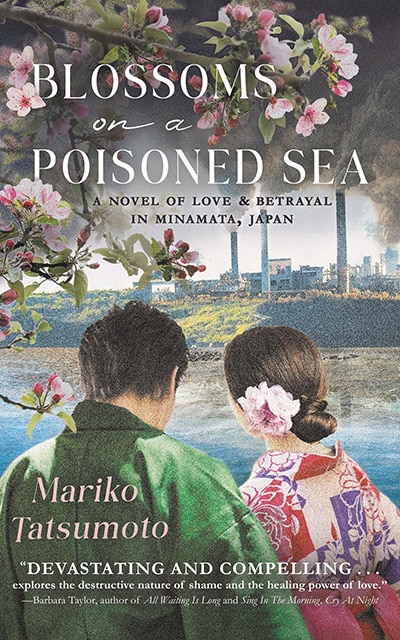

Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea: A Novel of Love & Betrayal in Minamata, Japan

(Northampton House Press)

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Key words: Pollution, activism, gender and class, romance

Yuki is the daughter of a poor fisherman. Kiyo is the son of a senior executive at Chisso, a huge chemical conglomerate. In 1956, they meet and become friends, then gradually fall in love. But then all living things in the once beautiful Minamata Bay suddenly die. The impoverished people living around it begin suffering from a terrifying disease that causes agonizing pain, paralysis, and death . . . including Yuki’s family. With no fish to catch and incapacitated from the disease, her parents are starving. As the sole wage earner, Yuki’s reduced to low-paying, backbreaking work as a laborer, then as a house cleaner.

The citydwellers, who work at Chisso, turn their backs on the lower-class fisherfolk, who largely tend to get the disease. The corporation stonewalls, denying culpability. Kiyo fails to convince his father to get the company to help. As the suffering spreads, Kiyo helps researchers find answers to the devastating neurological disease. But they’re blocked by the government and the corporate-influenced media.

Together Yuki and Kiyo must fight both the Japanese government and a powerful and ruthless corporation to save her family and the bay.

Blossoms on a Poisoned Sea: A Novel of Love and Betrayal in Minamata, Japan by Mariko Tatsumoto focuses on the discovery and impact of Minamata disease, named after the city in Kyushu, the most southerly of Japan’s four main islands, where it broke out in the late 1950s. The book’s subtitle—A Novel of Love and Betrayal—points toward the romantic relationship between its two principal characters, both fictional: Kiyo, a boy whose father handled waste disposal for the Chisso Corporation; and Yuki, a girl whose family fished in Minamata Bay and fell victim to the disease. It is also a novel about betrayal because Chisso Corporation, a manufacturer of fertilizers and plastics, knew that it was causing this painful disease yet continued to pollute Minamata Bay—and denied responsibility—for more than a decade. Befitting its subject, the novel has a dramatic plot and vivid characters.

The larger backdrop for Blossoms is the industrial development of modern Japan. Japan has experienced two periods of especially intense, fast-paced development: the late nineteenth century, when it industrialized quickly to forestall potential Western efforts to colonize it; and the mid-twentieth century, when it sought to rebuild after its devastating loss in World War II. Each of these periods of rapid development was marred by environmental disaster. During the first round, in Japan’s Meiji period (1868–1912), the Ashio Copper Mine north of Tokyo released waste that was contaminated with toxins like arsenic, poisoning fish, silkworms, and rice harvests downriver and causing hundreds of deaths. After World War II, the most notorious environmental disaster took place in Minamata in what the British medical journal Lancethas called “one of the most catastrophic incidences of industrial pollution the world has ever seen.”[1]

Minamata disease is caused by a substance called methylmercury. Chisso used inorganic mercury as a catalyst in an industrial process that created particularly nitrogen-rich fertilizers. Afterward, the mercury was discarded directly into the marine environment near the factory. Microorganisms in that environment converted this mercury into methylmercury—a form of organic mercury—that entered microscopic plankton in the water. Mussels, oysters, and fish such as anchovies fed on this plankton, concentrating the mercury in their bodies in the process. At the top of the food chain, people who consumed this seafood fell victim to the toxins it contained.

Minamata disease attacks the central nervous system, including the brain. Victims experience frequent convulsions; over time, they lose their ability to speak, and their vision becomes progressively narrower. Across the decades, more than 900 individuals are known to have died of the disease and over 12,000 have been officially recognized as victims despite bureaucratic obstacles to achieving this recognition. In Blossoms, several members of Yuki’s family experience its increasingly extreme effects.

The disease broke out first in cats—like Yuki’s cat Jiro—living in fishing villages just outside of Minamata. Cats were valued as predators, keeping the rat population under control; unchecked, rats were known to damage and even destroy expensive fishing nets. Area residents noticed that some cats were suffering from convulsions, which led to the disease being nicknamed the “dancing cat” disease. Indeed, we first encounter Kiyo and Yuki in separate early chapters of Blossoms as they watch cats convulsing and, in some cases, the cats ended up throwing themselves into the bay and drowned. Like numerous other details in Blossoms, such descriptions are historically accurate: Cats were the proverbial canary in the coal mine, presaging dangers to come.

As noted, the two lead characters of Blossoms are Kiyo (Kiyoshi) and Yuki (Yukiko). They meet when Kiyo rides his fancy new bike from Minamata, where he lives, to the impoverished village of Tsukinoura, where he encounters Yuki along the beach. Kiyo aspires to become a doctor. With his father’s help, he is apprenticed to Dr. Hosokawa Hajime (an actual historical figure) at Chisso Hospital, where he gains a front-row seat to the dramatic medical research taking place on this initially mysterious disease. Kiyo’s excitable activist personality calls to mind Joe Hardy of the classic Hardy Boys series.

Yuki, in turn, is talented as an artist but has few supplies, and no money for lessons to develop her skills. Her vivacious, headstrong personality calls to mind Anne Shirley in Anne of Green Gables, though some of her experiences—including being raped at her warehouse job in chapter 34—are more harrowing than Anne’s. Kiyo and Yuki, who are fourteen years old at the beginning of the book and eighteen years old by the end, believe in and trust each other. In the long term, each will be able to fulfill their dreams.

As they become friends (and then more), Kiyo visits Yuki’s family more often. He begins to help them with their financial challenges—for example, the loss of free seafood from the bay—and he learns more about their lives. The book frequently alternates between his experiences surrounded by wealth and hers surrounded by poverty. Indeed, at one point, he even mentally compares the smooth sake (rice wine) he tastes at home with the harsh shōchū (distilled spirit) he tastes at Yuki’s house. The accumulation of such comparisons provides a reminder to readers that despite Japan’s reputation as a largely middle-class country, not all Japanese have the same experiences or opportunities.

The practice of contrasting the lives of the rich and the poor is a long tradition in East Asia. For example, during China’s Tang dynasty (roughly 600–900 CE), the eminent poet Du Fu frequently returned to this theme. One famous short poem reads: “Behind the gates of the wealthy / food lies rotting from waste / Outside it’s the poor / who lie frozen to death.”[2] Reminiscent of this, one of Yuki’s jobs to make ends meet is working as a maid for the wealthy Sakagami family. She is quite surprised as she looks through their kitchen: “This single family pantry stocked more food than her village grocery store” (p. 328). The Oscar-winning movie Parasite (2019) by Korean director Bong Joon Ho offers a recent exploration of this theme.

Blossoms highlights the many obstacles to exposing and resolving the issue of methylmercury pollution in Minamata Bay. For example, Chisso Corporation insisted that it only dumped inorganic mercury into the Bay and, therefore, could not be responsible for the organic mercury in victims’ bodies. Scientists in the 1950s did not understand that inorganic mercury could become organic through interactions with microorganisms in water, so for a time this assertion stymied progress in establishing Chisso’s culpability. There were also other obstacles. For example, Chisso claimed—and Kiyo’s father argued—that Japan’s navy had dumped munitions from World War II into the bay after the war and that, as the casings of these munitions corroded, they were leaching poisons into the water (Chisso later admitted that it knew otherwise). There was also a strong attitude that Japan’s humiliating defeat in the war made economic development paramount. As Kiyo’s teenage friend Masa remarks, “Japanese have always sacrificed for the good of our people. So a few must suffer to make Japan a global power again, right?” (p. 207).

There was also a pervasive belief in Minamata—expressed by various characters in Blossoms—that disease victims were exaggerating or even faking their symptoms in order to receive government aid. In addition, there was fear that any publicity directed to the disease might discourage tourists from visiting, depressing the local economy. Kiyo’s father was particularly anxious that actions taken against the company might compel its factory to close—again, devastating the local economy. As a result, company managers, government officials, and newspaper owners all worked to suppress news about the disease, or failing that, to downplay its seriousness.

For families that fell victim to the disease, the saddest aspect was its effect on babies. Numerous babies were born with symptoms of the disease. At first, they were thought to be suffering from cerebral palsy, which has some similar characteristics. Over time, however, researchers proved that methylmercury caused these birth defects. In a pregnant woman’s body, the placenta usually nourishes the fetus while protecting it against exposure to toxins. However, methylmercury has the capacity to bypass the placenta’s defenses. As a result, the umbilical cord connecting the placenta to the fetus pumped mercury into the developing child while withdrawing it from the body of the mother. Accordingly, some mothers (like Yuki’s mother in Blossoms) had only mild cases, while their babies (like Yuki’s younger sister Tomoko) bore the full brunt of the poison. In some instances, the disease destroyed not only individuals but entire family lines—an especially tragic issue in Japanese culture.

In chapter 1 and again in the epilogue, the frame story is set in the 1970s—Kiyo and Yuki as adults with children of their own. In that period, environmental activists won a major court case against Chisso. This led the company to pay, over time, well over a billion dollars to defray the costs of Minamata Bay reclamation and victims’ medical expenses. (Note that the book gives financial sums in yen only. In the late 1950s, 360 yen equaled one US dollar.) Chisso remains a major employer in Minamata to this day.

Japan is not the only country to have experienced mercury pollution. For example, in the late 1960s in the Canadian province of Ontario, mercury discharge from a paper mill contaminated the fish that two First Nations (Native) communities relied on for food. In China in the early 1960s, the Wanshan mine in Guizhou province caused the mercury poisoning of some of its workers and polluted the nearby rice fields. The Wanshan mine closed in 2001, but China today is the largest producer, consumer, and emitter of mercury, accounting for about half of global use. In sum, the tale told in Blossoms has a twofold significance: Even as it sheds light on the sacrifices made in the course of Japan’s rapid economic development, it links to larger themes of industrial pollution worldwide.

A note regarding the text: Japanese words are used in the novel, sometimes with explanations and sometimes without. Readers will be familiar with words such as yakuza and sensei, which appear in the English dictionary and are no longer italicized. It’s worth pointing out, however, that doctors are also called “sensei” by the book’s characters as a reflection of the real-life use of the term in Japan. Also, young male characters are often called –kun (as in Masa-kun). Young female characters, in turn, are often called –chan (as in Tomoko-chan).

Author: Professor David B. Gordon, Shepherd University

2025

[1] Justin McCurry, “Japan remembers Minamata,” Lancet 367 (2006): 99–100.https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(06)67944-0/fulltext

[2] Quoted in https://allpoetry.com/Behind-The-Gates-Of-The-Wealthy.