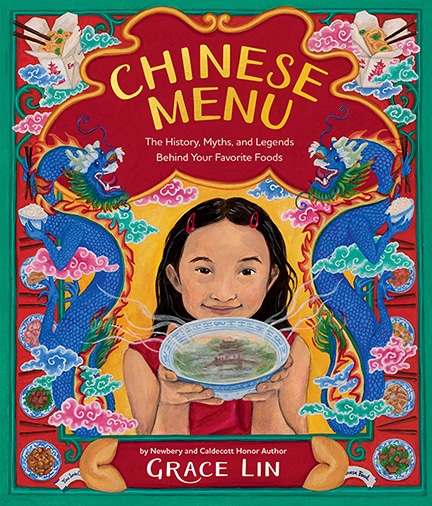

Chinese Menu: The History, Myths and Legends Behind Your Favorite Foods

(Little, Brown and Company Books for Young Readers)

- Non-fiction

- Set in China

Key words: Folklore, cooking, food, idioms

From fried dumplings to fortune cookies, here are the tales behind your favorite foods.

Do you know the stories behind delectable dishes—like the fun connection between scallion pancakes and pizza? Or how dumplings cured a village’s frostbitten ears? Or how wonton soup tells about the creation of the world?

Separated into courses like a Chinese menu, these tales—based in real history and folklore—are filled with squabbling dragons, magical fruits, and hungry monks. This book will bring you to far-off times and marvelous places, all while making your mouth water. And, along the way, you might just discover a deeper understanding of the resilience and triumph behind this food, and what makes it undeniably American.

Award-winning and bestselling author Grace Lin provides a visual and storytelling feast as she gives insight on the history, legends, and myths behind your favorite American Chinese dishes.

“These stories are real. They are real legends, real myths, and real histories.”

—Chinese Menu (p. 7)

Appropriate for Grades: 3–12

Best for Grades: 3–10

Introduction to the Book

Chinese Menu does not interrogate deep cultural issues of assimilation, immigration, or historical bias. Rather, the book is exactly as the author Grace Lin explains: by design, a menu-style introduction to the stories underlying many Chinese restaurant dishes that are familiar to Americans. As such, each story is quite short and can be read independently, making for an excellent read-aloud collection or a means of introducing myriad unit concepts or themes.

Best Matched Curricular Units

- Myth and Legend (Language Arts)

- Legend vs. History (History)

- Illustration (Art)

- Human Migration (Humanities)

Essential Questions

- How can food bring cultures together?

- How can food affect events and history?

- Why does food carry so much information?

Note to Teachers: This book is packed with Mandarin Chinese names for people, places, and food. Since the stories are so short, there is not much time to get used to pronouncing one set of names before a new group of characters and places is introduced. Thus, a teacher unfamiliar with Mandarin may find it challenging to accurately pronounce many words. This may be seen as an opportunity to demonstrate humility, explaining the linguistic challenges inherent in sharing stories across cultures. If the class has a fluent Mandarin speaker who is interested in helping with the pronunciations, all the better!

Suggested Activities

Menu-Based Free-Read (pp. 5–6). Select one dish from each section of the menu (one tea variety, one appetizer, and so on). Read the menu selections and complete an activity appropriate to the unit. Adjust the length of the activity by keeping or removing parts of the menu (for example, reserve the Desserts section as an extension activity for stronger readers).

Class Menu Jigsaw (pp. 5–6). Groups are assigned a part of the menu from which they must select a specific dish. Each group completes a read-around for their selected dishes. After they complete their readings, each group gives some sort of presentation to the class (for example, they could make a slideshow, draw a picture, or introduce the dish with a summary of their story).

Food Map Research (p. 9). Select a province from China and research its culinary preferences and specialties. Pay attention to how natural geography affects these preferences. If there is a Chinese restaurant in your town that specializes in the cuisine of that province, present the menu to the class and discuss.

Food Timeline: Open Discussion (pp. 10–11). Prior to reading the stories, explore the Food Timeline (in groups or as a class) to inspire curiosity and predictions (for example, why does the number of dishes seem to increase so much beginning with the Song dynasty?). Note: This book will likely leave most questions unanswered; nevertheless, these could spark a number of different investigative learning experiences.

History, Myth, or Legend. On the wall, post a “Fact Meter” that ranges from Least Factual to Most Factual. Discuss the differences between history, myth, and legend; as a class, come to a consensus as to where each should be placed on the Fact Meter.

Because the author often specifies whether each story is legend, myth, or history, read them without their introductions. After reading each story, have students place the title on the Fact Meter. Another worthwhile discussion in such a unit is the movement of stories from one position to another based on when an audience hears them.

Illustration Predictions. In conjunction with the name of a dish, use the illustrations before reading the stories to predict something about the dish and/or its history. After reading, discuss the accuracy of the predictions.

Dish Self-Portrait. Select a favorite dish (it could be from a Chinese menu at a local restaurant or a family cultural favorite). Following the author’s model that precedes the introductions to each section of the book (pp. 13, 31, 63, 91, 119, 152, and 231), paint, draw, or color a self-portrait that includes the student, their chosen dish, the name of the dish in both English and the language of origin for the dish, and a thoughtful border design.

Traditional Chinese Character Dish Illustration. “Chinese characters” is the English term for written Chinese. Every single section and dish in the book includes a Chinese characters and their translation. Ask students to choose their favorite dish and then practice copying the characters for that dish several times. They are not aiming for accurate stroke order or perfect replication of the printed character; instead, they are simply trying to become familiar with the shapes and lines within the characters. After they are comfortable with the look and feel of the characters, ask them to hide them inside an illustration of that dish. The class could go on a gallery walk to see if they can find these characters inside one another’s illustrations.

Discussions

Because this book offers such wide variety of stories, ranging from fantastical to apocryphal to loosely factual, it does not easily lend itself to specific discussion topics. In many ways, this is an advantage because a teacher could make any number of these wide-ranging tales fit the theme of many different units, even some that are not focused on Chinese culture. A sampling of unit topics sprinkled throughout the book includes Buddhism (The Origin of Tea, p. 59), gender roles (Crossing the Bridge Noodle Soup, p. 101), human impacts on nature (Bird’s Nest Soup, p. 111), and forced assimilation (Knife Cut Noodles, p. 141).

Although the design of the book lends itself to the introduction of broader units, it could well be used as a core text in conjunction with a World Studies unit on human migration, acculturation, or geopolitics. The author leaves such topics at the periphery, yet her book is a perfect springboard into wide-ranging discussions or research projects: for example, the author’s own relationship to the cultures represented, the alteration of dishes in relation to geographical movement, or the removal of history from the experience of eating.

Author: Josh Foster, Educator and Learner

2025