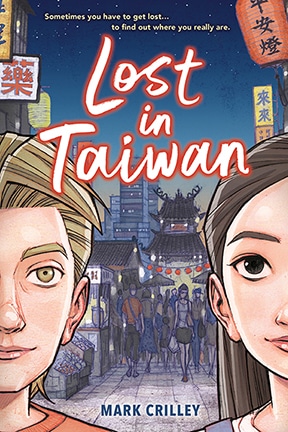

Lost in Taiwan

(LBInk/Little, Brown and Company)

- Fiction

- Set in Taiwan

Key words: Contemporary, identity, empathy, exploration

THIS WASN’T PAUL’S IDEA.

The last thing he’s interested in is exploring new countries or experiencing anything that might be described as “cultural enrichment.” But like it or not, he’s stuck with his brother, Theo, for two weeks in Taiwan, a place that—while fascinating to Theo—holds no interest to Paul at all.

While on a short trip to a local electronics store, Paul becomes hopelessly lost in Taiwan’s twisting, narrow streets, and he has no choice but to explore this new environment in his quest to find his way back to Theo’s apartment.

In an unfamiliar place with no friends—and no GPS!—there’s no telling what adventures he could happen upon. And who knows? Maybe it turns out he has friends in Taiwan, after all.

Lost in Taiwan by Mark Crilley is a graphic novel set in Taiwan, an island nation located about eighty miles off the southeast coast of the People’s Republic of China. Over the course of the novel, the protagonist, a college student named Paul, shifts from being a cranky, unwilling visitor to Taiwan to becoming a huge fan. Before looking at Paul and his conversion, it is first helpful to learn a bit about the island where Paul becomes lost.

Taiwan is a largely tropical island about 230 miles long, from north to south, and about 100 miles across. Its land area is slightly greater than the state of Maryland. Most of Taiwan is mountainous, and most of the population lives on its relatively flat west coast.

Historically, it has tended to serve as a frontier of Chinese civilization—for example, when a rebel plotting against the Qing (pronounced: ching) dynasty set up operations there in the seventeenth century. Much later, Taiwan formed an integral part of the Japanese empire as a colony for fifty years (1895–1945). Japan surrendered to the Republic of China at the end of the Second World War. But in the struggle for power in China in the years after the war, Nationalist (ROC) forces lost to Communist forces, retreating to Taiwan in 1949.

Today, the “Republic of China, Taiwan,” as it calls itself, consists of Taiwan and several small outlying islands. It is a democracy with two major parties: the Democratic Progressive Party and the Nationalist Party. The former supports formal independence for Taiwan, while the latter seeks autonomy from mainland China at the very least. Mainland China (People’s Republic of China) holds that the territory of Taiwan belongs to China and continually presses for reunification. Meanwhile, the official position of the U.S. government is that Taiwan’s status remains unresolved.

These issues are nowhere in the consciousness of Paul, the protagonist, and are not referred to by other characters in Lost in Taiwan because the book’s aim is, instead, to provide the reader with a taste of Taiwan’s everyday life. Paul is visiting his brother Theo and, at first, is unconcerned with Taiwan’s everyday life: He spends his days on the couch in his brother’s apartment, eating McDonald’s and playing video games. He is self-absorbed and resentful of his brother, who has been living in Taiwan, studying Mandarin Chinese, and dating a Taiwanese woman.

When Theo leaves for an overnight trip, Paul decides to venture out to buy a special video console, sold in a local store in the city of Changbei. As he starts walking back from the store, he accidentally drops his phone into a sewer, ruining it. At this point, he meets Peijing, who shows him around the city, introducing him to its food, drink, scenery, and customs. Peijing’s cousin, Wallace (Chinese name: Zhiqiang), helps introduce Paul to places and situations he had not imagined.

While the city of Changbei appears to be fictional, Lost in Taiwan’s visual depictions of moped-filled streets, small shops, covered arcades, picturesque country fields, gentry-style traditional rural compounds, and so on, accurately reflect the outskirts of one of Taiwan’s cities.

The story’s pivotal moment occurs when Peijing introduces herself to help Paul find his way back to his brother’s apartment. This may seem far-fetched, but Taiwan is especially friendly, a quality that not only Westerners but also visitors from around the Chinese-speaking world have noted. Indeed, the behavior of many Taiwanese expresses both the classic ideal of the Confucian gentleman and the contemporary Western ideal of civic-mindedness. If an individual appears lost in one of Taiwan’s cities, it is likely that someone will do their best to provide assistance.

Despite her clear friendliness—and undertones of a possible budding romance—Peijing is critical of Paul. At one point, she takes part in a divination ritual at a Chinese folk temple. Watching, Paul tells her that it feels like he’s entered “The Wizard of Oz or something”; whereas people in the U.S. simply do “ordinary, everyday stuff,” everything in Taiwan seems “super exotic.” She is angered by this, pointing out that his culture is not the “normal” one, nor hers the “weird” one (pp. 116–117).

Later, he will tell Peijing that he lacks friends (beyond online friends) because he tends to leave friendships when problems arise rather than trying to resolve them. Peijing maintains that this is a fear-based approach and that he ought to reconsider. Regarding both criticisms, Paul shows a willingness to reassess his attitude, making this graphic novel a bit of a coming-of-age story with relevance beyond its explicit focus on Taiwan.

The divination ritual that Peijing participated in involves throwing a pair of moon-shaped blocks (jiaobei) on the floor and watching to see how they land: both face up, both face down, or one facing up and one facing down. The last option suggests that the god being addressed will grant the supplicant’s wish, though for a major request, it is best if this positive answer occurs three times in a row.

Cranes appear at several points in Lost in Taiwan. First, when Paul and Peijing visit Peijing’s grandfather’s house in the countryside, Paul admires a depiction of a crane that her grandfather had painted. Later in the story, Paul buys a cork carving of a crane for Peijing as a thank-you gift. After he wakes up the following morning (having spent the night at Wallace’s apartment), he sees an actual crane standing in a nearby rice field. In Chinese tradition, cranes have a range of auspicious meanings, such as longevity, nobility, purity, and good fortune.

At a few points in the book, Paul’s brother speaks with his girlfriend in Chinese, and these lines of dialogue appear in Chinese characters. Specifically, these are the traditional characters used in Taiwan and Hong Kong, as opposed to the simplified characters used in mainland China.

In the text, Chinese words sometimes appear in the newer romanization system, called pinyin, which is standard in mainland China. For example, Wallace’s Chinese name, Zhiqiang (pronounced: JER-chyang), uses the pinyin system. Since 2009, pinyin has served as the official system of romanization for Taiwan. However, other terms like “Kaohsiung”—the name of a major city in southern Taiwan—are spelled using an older system, called Wade-Giles. In Taiwan itself, as in Lost in Taiwan, the two systems of transliteration exist side by side.

Author: Professor David B. Gordon, Shepherd University

2025

So much of my life is about avoiding failure. Avoiding it by…not even trying to do anything in the first place.

—Lost in Taiwan (p. 234)

Appropriate for Grades: 6–9

Best for Grades: 6–7

Introduction to the Book

Lost in Taiwan takes readers on a whip-fast ride from the heart of Taipei, Taiwan, into its rural outskirts. With illustrations that bring to life the city streets and alleyways, this book serves as a great introduction to the tourist experience of Taiwan; the steaming dumplings and cups of tea; the architecture; and the generous, welcoming nature of the culture. It is the kind of book that will excite students to explore more about the country and maybe even inspire a desire to visit.

Since the protagonist, Paul, is a newcomer with no background knowledge of Taiwan, readers are also able to leap right into this story without needing any background knowledge regarding the language or the geopolitics of Taiwan. The story does not delve into the complexities of the region, and when a word written or spoken in Mandarin is used, the characters help the reader make sense of it.

Best Matched Curricular Units

- Empathy for Strangers (Humanities)

- Map Skills (Geography)

- Introduction to Taiwan (World Studies)

Essential Questions

- How can we best explore the world?

- What kinds of friendships add value to our lives?

- How can language bridge cultures?

Suggested Activities

Cover Predictions. Before reading the book, ask the students to take a close look at the cover. Students might raise questions about the story (for example: What is the black stove-type thing? What happens inside the building? How old is the tree? Are the boy and girl siblings or friends or something else?). After reading the book, discuss which of those questions have been answered.

Foreshadowing. The book begins with nine pages of illustrations that foreshadow the storyline. In addition, every chapter starts with an illustration on the opening page (for example, a scooter to begin chapter 2). Students can predict how each chapter illustration will connect to the plot. After they finish reading the chapter, discuss which predictions were correct, and explore why students believe the author chose that particular object to illustrate the chapter. Would they have selected a different “foreshadowing object” if they had illustrated the book?

Research the Irony. Peijing says she dreams of opening an English-style teahouse in Taiwan, a dream with incredible historical irony. Research the origins of tea in England, how the English got a taste for it, and how it shaped the British empire’s colonial rule, specifically in China. Can students see the irony in an English-style teahouse opening in Taiwan? Can the students create any similar examples of irony for a young Taiwanese dreamer (or a young dreamer from another cultural background)?

Suggested Discussion/Writing Prompts

To Translate or Not to Translate. Throughout the book, the author chooses to use the traditional Chinese script when a character speaks in Mandarin. He could have chosen to translate their words and then indicate the language was spoken in Mandarin by altering the script (for example, by using a different font, color or italics), but he does not. Why would the author elect to keep the words untranslated for a readership who will most likely be unable to read them? How does it benefit the story? If the technology is available, choose a page with Chinese script and translate it. How does having the translation available alter the reader’s experience?

Coca-Cola Symbolism. On pp. 132–133, we learn how Coca-Cola is translated into Chinese script for use in Taiwanese advertising. The author illustrates a can of Coca-Cola in the final two-page spread of the entire book (pp. 244–245). What do students believe is the symbolism here? Consider the prominence of the character 樂 (le), meaning happiness, as well as the company’s country of origin.

A good reference for further study and lesson plans is Centering Taiwan in Global Asia, a K-14 Curriculum Resource About Taiwan (https://centeringtaiwan.pitt.edu/).

Author: Josh Foster, Educator and Learner

2025