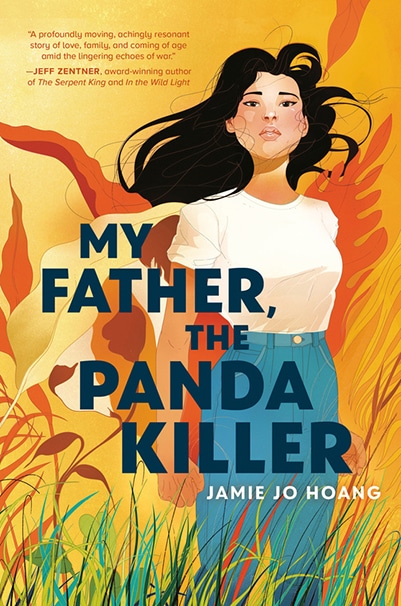

My Father, the Panda Killer

(Crown Books for Young Readers)

- Fiction

- Set in Vietnam and America

Key words: Contemporary, refugees, abuse, resilience

San Jose, 1999. Jane knows her Vietnamese dad can’t control his temper. Lost in a stupid daydream, she forgot to pick up her seven-year-old brother, Paul, from school. Inside their home, she hands her dad the stick he hits her with. This is how it’s always been. She deserves this. Not because she forgot to pick up Paul, but because at the end of the summer she’s going to leave him when she goes away to college. As Paul retreats inward, Jane realizes she must explain where their dad’s anger comes from. The problem is, she doesn’t quite understand it herself.

Đà Nẵng, 1975. Phúc (pronounced /fo͞ok/, rhymes with duke) is eleven the first time his mother walks him through a field of mines he’s always been warned never to enter. Guided by cracks of moonlight, Phúc moves past fallen airplanes and battle debris to a refugee boat. But before the sun even has a chance to rise, more than half the people aboard will perish. This is only the beginning of Phúc’s perilous journey across the Pacific, which will be fraught with Thai pirates, an unrelenting ocean, starvation, hallucination, and the unfortunate murder of a panda.

Told in the alternating voices of Jane and Phúc, My Father, The Panda Killer is an unflinching story about war and its impact across multiple generations, and how one American teenager forges a path toward accepting her heritage and herself.

This book will trouble you long after you’ve put it down. You may even need to stop a few times to absorb the enormity of what you have just read. It took me a long time to determine why this book bothered me so much, but I think it is because the narrators are children, aged eleven and eighteen. Despite these warnings, My Father the Panda Killer by Jamie Jo Hoang is a book that you need to share with your students in 11th and 12th grades.

The narrative is engaging and fast-paced, as you wonder if Jane, the eighteen-year-old, will be permitted to move away from home and go to college. But this is no straightforward coming-of-age story, as Jane’s story alternates with that of her father’s, Phuc (rhymes with duke), who escaped the war in Vietnam in 1975, when he was only eleven. Alone, he faced starvation and unspeakable horrors that no one, especially a child, should face. I alternated between feeling great sympathy for Phuc as a refugee with a traumatic past and great anger at his behavior in the present when he beats his children for even the slightest transgression. Jane’s mother, Ngoc Lan, has abandoned the family, and later it becomes clearer as to why, but it is hard to feel sympathy for her. She knows her husband is, at times, an abusive and angry man, and yet she leaves her children with no sense of why she left them or where she has gone, a devastating loss for Jane and her brother, Paul. The true subject of this book is intergenerational trauma, and as challenging as it to read, I highly recommend this book, with some important caveats.

Teaching in a Title I high school in Pennsylvania, I recognize that this book echoes the lives of many of my students. It is nearly impossible to get the very students who need the camaraderie and support of after-school sports and activities to attend because, like Jane, most of them work to help support their families. Like Jane, most of our students are the first generation in their family to complete high school; college is an option, but

FAFSA applications for financial aid can be a challenge when parents are paid “under the table.” They may not have access to the kinds of documentation required to complete such paperwork. On a personal level, they know firsthand the kinds of behaviors Phuc exhibits—a strange combination of love, anger, and corporal punishment. Many of students are embarrassed by their heritage, just like Jane, who, along with her best friend Jackie, do all they can to distance themselves from other immigrants, especially those who still speak their native language and eat traditional foods.

Because of the strong parallels between the characters and the students with whom I will read and discuss this text, securing approval from the school administration was vital. Our Curriculum Council meets regularly, and our district is open to books that speak directly to students. I would suggest having an alternative text for students who choose not to read this book as it could trigger some very strong emotions. While there is great beauty in the narrative at points, the author does not shy away from vivid descriptions of death, war, cruelty, and the impact of witnessing these events. Reading the chapters about Phuc and the panda, knowing from the title that the panda will die, brought me to tears. The story describes the connection between Phuc and the panda, their affection for one another, and what leads Phuc to have to kill the panda or be killed. This event clarifies in many ways why Phuc is the kind of father he is, and yet, even with all that he has witnessed, he, like all adults, has a choice as to how he will behave and treat his own children. Ultimately, he fails both his children. At one point, following her father’s example, Jane injures her much younger brother, Paul, but later makes a conscious decision to never hurt him again. That said, I am still at a loss as to why she does not do more to stop her father from beating her little brother. I understand the harsh reality that the foster system is often worse than the situation a child may be experiencing at home. This is a book that raises a lot of hard questions and, like real life, does not offer solutions, only coping mechanisms that may not be ideal.

Our district has a supportive Guidance department as well as social workers. During homeroom, we offer a Social Emotional Learning program that provides short videos, workbook exercises, and a teaching guide with discussion points. The lessons cover everything from how to understand the grading system to how to introduce yourself in a variety of settings. It fosters a sense of belonging and understanding within the group. If students are able to trust one another in sharing their opinions and thoughts, this program could offer a safe space for students who are living with abuse in their homes. The homeroom teacher may need the support of other appropriate school personnel insofar as the information shared by students may need to be reported.

The structure of the text with its alternating chapters is interesting, and determining how each chapter relates to one another is worth exploring. Students could be split into two groups, with one group instructed to read only the chapters dealing with Phuc, with the other group focused on Jane’s chapters. Students could then compare the narratives and see how reading the other chapters changes their understanding of these two characters.

Food plays a significant role throughout the text, from the purchasing of ingredients to the preparation of both Vietnamese and American foods. What kinds of experiences do students have with food in their families? Who does the cooking, cleaning, and planning for meals? How does this reflect the structure of the family?

Echoing the experience of the author, Jane can find no resources to help her learn about the Vietnam War from the perspective of the Vietnamese. All she knows is based on the fragments Phuc mentions when speaking to friends and family, and that is only when she is brave enough to eavesdrop. This is another significant lesson: the difficulty of finding information about an event from a perspective outside American news and publications. Students should consider how their viewpoint of an event might change if they were learning about it from news outlets in Vietnam, for example, as opposed to American news outlets. Students who are bilingual could explore a topic by comparing the American perspective to that of another part of the world.

Overall, the book lends itself to close reading and offers the educator the opportunity to show students how to be active readers by taking notes and creating a vocabulary list, complete with definitions of unfamiliar and new words. The book includes a glossary of characters. In the Author’s Note, Jamie Jo Hoang reflects on writing about her own experiences. She notes that she is working on a continuation of the story of these characters through the voices of Paul and his mother. Asking students to consider what that narrative might address could be an interesting creative writing exercise.

My Father the Panda Killer is an important book. Jane, Phuc, and Paul are survivors. Ultimately, it is a story of hope, determination, and overcoming obstacles. It demonstrates the impact of war on those who have experienced it firsthand, and how it affects even those who never experienced war themselves but love someone who did.

Author: Kachina Leigh, high school art and AP art history teacher

2024