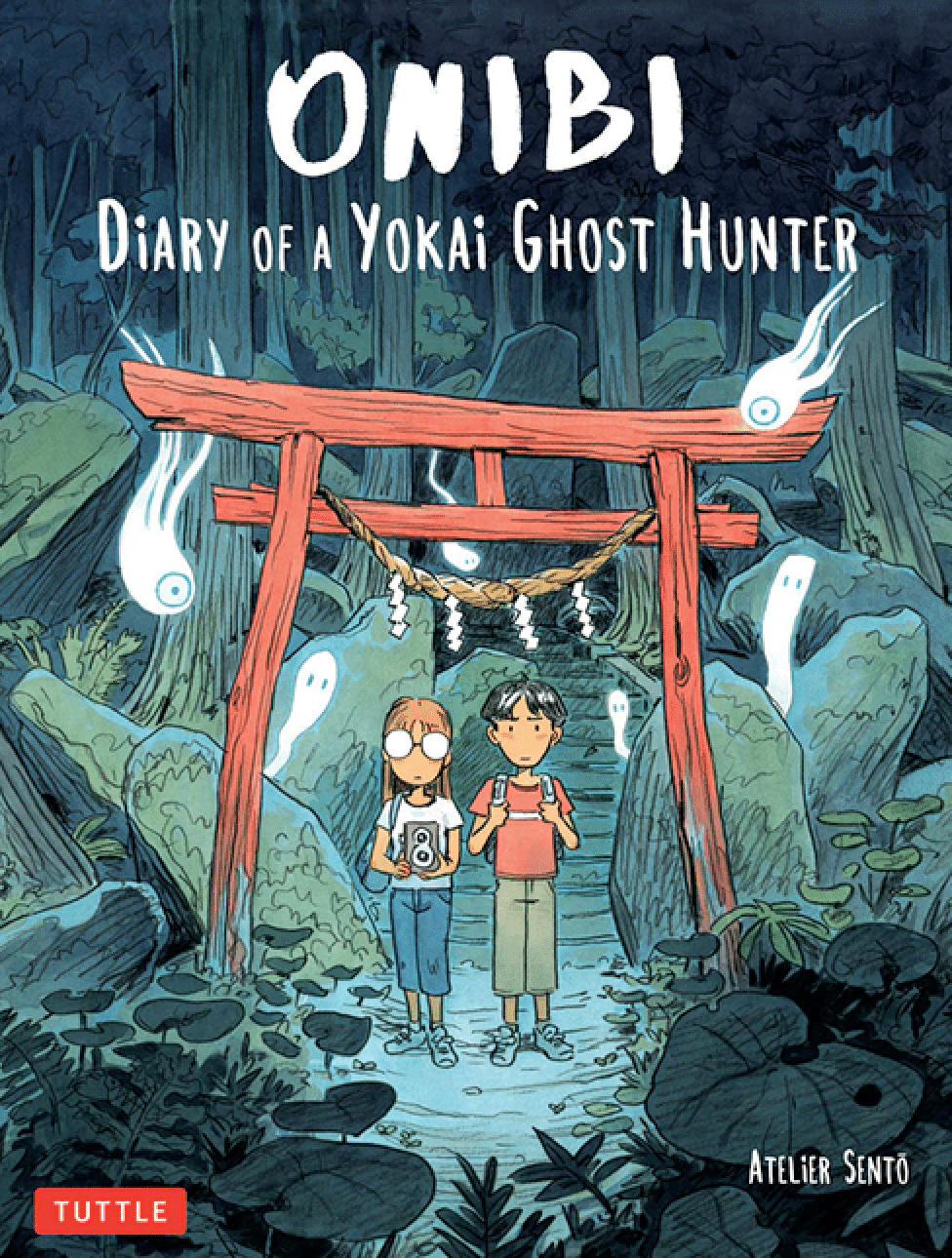

Onibi: Diary of a Yokai Ghost Hunter

- Fiction

- Set in Japan

Keywords: graphic novel, translation, supernatural, folklore, adventure

Part fantasy, part travelogue—this graphic novel transports readers to the intersection of the natural and supernatural worlds.

Onibi: Diary of a Yokai Ghost Hunter follows the adventures of two young foreigners as they travel to a remote and mysterious corner of Japan. Along the way, they purchase an old camera that has the unique ability to capture images of Japan’s invisible spirit world. Armed with their magical camera, they explore the countryside and meet people who tell them about the forgotten ghosts, ghouls and demons who lie in wait ready to play tricks on them. These Yokai, or supernatural beings, are sometimes kind, sometimes mischievous, and sometimes downright dangerous!

The Supernatural in Japan

Japanese culture, folklore, and religious systems have more manifestations of the supernatural than perhaps any other culture. This is partially due to the concept in Shintō that all things are to some degree alive. But Buddhism and ideas and stories imported from abroad also add to this rich cultural heritage. Even today, the supernatural are hugely popular with the Japanese public, appearing in books, scholarly theses, manga, movies, anime, video games and other areas of popular culture. Many of the characters and situations that students experience in video games come from the Japanese supernatural.

Places Mentioned in the Book

Niigata prefecture 新潟県 (Pronounced: knee-EE-gah-tah)

Japan is divided into prefectures, which are similar to states in the U.S. Niigata prefecture is located on the Sea of Japan side of Japan, on the main island of Honshu (pronounced: HONE-shoe). The city of Niigata is the third largest city on the Sea of Japan side. The major industry is agriculture, particularly rice.

Sado Island 佐渡島 (Pronounced: sah-DOUGH)

Sado Island is located off the coast of Niigata and is the largest island in the Sea of Japan. It was once a place of exile for Japanese. Prominent exiled figures include Emperor Juntoku, the Buddhist monk Nichiren, and the founder of Noh theater, Zeami Motokiyo. Today one of Sado Island’s most well-known attractions is the Earth Celebration, a festival hosted by the taiko group Kodo, who are world renowned.

Onsen 温泉 (Pronounced: OWN-sehn)

The islands of Japan are dotted with hot springs. Bathhouses have been built over and around these hot springs, attracting tourists and locals alike. These are called onsen, and are often featured on Japanese television travel shows, as many boast of special types of mineral waters and other features. A typical onsenmight include a variety of services, including a gift shop, cafeteria, dining halls, massage, drink machines, and television. Bathing rooms are usually divided into male and female. Each section will have a dressing room with lockers and areas to bathe before going into the baths (complete with shampoo and soap). Once a person is clean, they can enter the rooms with the hot baths, and choose from a variety of hot temperatures. Bathing areas might be indoors or outdoors (discreetly fenced off from prying eyes) and are large and meant to be communal. Soaking in onsen is considered to be both therapeutic and relaxing.

Religion in the Supernatural

Temples vs. Shrines

The two major faith systems of Japan that date back centuries are Buddhism and Shintoism. Buddhism came from India via China and Korea to Japan, and Shintō is the indigenous faith, and a form of nature worship based on the feeling that all things are animate and sentient. Both existed intertwined in Japan for centuries until the late 1800s. A Buddhist complex is called a temple and a Shinto complex is called a shrine.

Torii 鳥居 (Pronounced: toe-REE)

This term literally means “bird perch.” It is a Shintō ceremonial gateway usually constructed of wood. The design is simple, with two vertical cylindrical posts surmounted by two horizontal posts. The upper horizontal post is rectangular but beveled in the upper surface to shed rain. The lower one is simply rectangular. Anytime you see a torii, it denotes sacred space.

Torii often appear at Buddhist temples, as the Shintō and Buddhist systems were intertwined for centuries, and not clearly set apart until the late nineteenth century.

Jizō 地蔵 (Pronounced: gee-ZOH)

Jizō is a Buddhist deity, a bodhisattva (Japanese: bosatsu) or enlightened being who forgoes nirvana in order to bring Buddhist salvation to others. Jizō is the protector of children and pregnant women in particular. In Japan, Jizō is often depicted in the garb of a monk, with a shaved head. These figures are often seen with bibs, as worshippers donate bibs to the Jizō statues, along with children’s toys and clothes. Worshippers also donate prayers that deceased children will travel safely with Jizō into an afterlife. Jizō may appear in groups at Buddhist temples or even alone along mountain trails or rural roads.

Supernatural Terms Used in the Book

Yōkai 妖怪 (Pronounced: YOH-kai)

These are what we might call the entire realm of ghosts and demons. Within this larger category, there are all sorts of manifestations, from animals such as foxes (see below) to human ghosts, to inanimate objects that come alive.

Yūrei 幽霊 (Pronounced: YOU-ray)

The yūrei is a human ghost, often but not exclusively a female ghost. It was thought long ago that if a person died violently or had been cruelly abused, or died while experiencing emotional angst, then their spirit would be trapped between this world and the other. The yūrei might be the crying ghost of a young woman who had been abused by her master, for example. More typically, the yūrei tends to be an angry spirit, bent on revenge, for wrongs that have not been righted. She is usually depicted in Japanese art as having long hair, a white robe, and no feet. She floats in the air or can appear in the face of a paper lantern or other places.

Foxes (kitsune) 狐 (Pronounced: kit-SUE-neh)

Japanese foxes have long been considered to be one of the two Tricksters in Japanese lore, along with the “raccoon-dogs” or tanuki 狸 (pronounced: TAH-new-key). Both animals are native to Japan and were thought to be able to transform into other shapes (shapeshifters) and bewitch humans with their Trickster ways. Foxes in particular were known for appearing as Buddhist nuns or monks, or as beautiful women, with the object of tricking humans or luring men to their death. Unlike the archetype Trickster that often alternates between good and bad deeds (the American Coyote is a prime example), the Japanese Trickster is more often harmful than good. However, there is a story of a fox who was rescued by a man from hunters, and then came to the man transformed into a beautiful woman. She married her savior, gave birth to a child, and then eventually shapeshifted back into her fox form, leaving him with the gift of the child as a thank you.

Foxes are also connected to the Shintō deity Inari, the deity of agriculture, particularly rice cultivation which is a staple food of Japan. Thus, fox statutes will be found alone or in groups at Inari shrines, or sometimes even by themselves along a forest road or village street. In this context, the fox is considered to be a messenger of Inari and is benevolent.

Onibi 鬼火 (Pronounced: oh-KNEE-bee)

A will-o’-the-wisp. The Japanese literally reads “demon fire.” It is a type of ghostly light. One of the types of onibi is the kitsunebi, which is the fox fire of Japanese lore. The fox fire is a hypnotic lure that leads travelers astray from the road on which they are traveling. Foxes are thought to be seen with balls of light or fire, particularly at night in graveyards.

Food

Onigiri お握り(Pronounced: oh-KNEE-gee-ree)

Balls of Japanese sticky rice have been a staple of travelers since the Tokugawa (Edo) Period in Japan (1615-1868). Onigiri traveled well, as they could be wrapped in seaweed and eaten while on the road. They also can contain cooked vegetables, meat, fish, or preserved or pickled fruit in the center, making for a light meal. Today you can buy onigiri everywhere in Japan, from convenience stores to large supermarkets. It is a stable snack food and children in particular are fond of onigiri. It is one of the preferred foods of foxes in Japanese lore.

Tempura udon 天ぷらうどん (Pronounced: ten-PUH-RAH OO-dohn)

Tempura is vegetables, herbs, meat, or fish fried in a very light batter. This dish originally came from Portugal but was refined over the centuries to have a particularly Japanese flavor and appearance. Udon are thick, chewy Japanese noodles made from wheat, and they can be flat or rounded. The two together are a dish served in broth, with the tempura on the top, in a bowl.

Author: Brenda G. Jordan, director of the University of Pittsburgh coordinating site for the NCTA

2021

Summary

The graphic novel Onibi: Diary of a Yokai Ghost Hunter tells the tale of two friends (stand-ins for authors Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard) during a trip to Niigata (pronounced: knee-EE-GAH-tah) prefecture in Japan. Their trip takes an odd turn right away, when one of the characters purchases a “Yokai camera” (pronounced: YOO-kah-ee) from an odd store. From there, the protagonists travel to different locations in search of the spiritual and supernatural, hoping to locate and document a side of Japan rarely seen by tourists. Traveling to Shinto shrines, natural landscapes, and landmarks, and finally ending up in front of a statue on the island of Jizō (pronounced: jee-ZOH), they discover aspects of Japanese mythology and begin to view the Land of the Rising Sun in a very different light.

Analysis

Onibi (pronounced: oh-KNEE-bee) does not provide the reader with any easy answers, leaving the supernatural shrouded in mystery at the end of each chapter. The graphic novel provides a multilayered reading, using text and dialogue to explain aspects of Niigata prefecture and Sado Island (pronounced: SAH-dough), panel art to communicate the natural beauty and supernatural eeriness of each setting, and the sections before each new chapter to connect the tales and imagination of the story with the real world. The approach used to express the intention and themes of the book—folklore, cultural communication and diffusion—not only gives the reader a sense that they are learning about things that are altogether unfamiliar to Western rationalism, but also that these things should be appreciated for their distinct “Japanese-ness.”

The Spiritual and the Supernatural

In Japan, some people believe in the existence of spirits known as yōkai (spirits/monsters) and yūrei (ghosts; pronounced: YOU-ray). According to Shinto, the indigenous belief system of Japan, nature spirits known as kami (pronounced: KAH-me) have their own individual personalities, and they may be attached to objects or specific aspects of the natural landscape. This belief in multiple deities or spirits pervades Japanese Buddhist cosmology as well, which has drawn on Shinto kami while introducing divine figures from Indian and Chinese Buddhism, known as bodhisattvas. Given all these instances of spirits in Japanese belief systems, the supernatural has become embedded in the Japanese culture. When the protagonists of Onibi explore particular sights and aspects of the area they are staying, they do not experience anything out of the ordinary in comparison with what they might encounter in other parts of Japan. Within the story, the protagonists even refer to specific kinds of spirits, or representations of spirits. The first are the kitsune (pronounced: key-TSU-neh), trickster spirits in the guise of foxes that are usually associated with the harvest deity Inari (pronounced: ee-NAH-ri). The second are the statues representing Jizō Bosatsu (pronounced: jee-ZOH BOH-sah-tsu), a Buddhist bodhisattva who ensures that the souls of the recently deceased, especially young children, gain safe passage to the spirit world. The inclusion of these and other kinds of local spirits of Niigata prefecture create a portrait of a country with a deep history and appreciation for the role of the supernatural in daily life.

Appropriate Grade Levels

Depending on the grade level, the book can be used on all three levels: elementary, middle, and high school.

- Elementary: 4th grade

- Middle school: 7th/8th grade

- High school: 9th/10th grade (possibly 11th grade, depending on the depth of analysis the teacher would like to pursue)

Activities

- Reading and Discussion: Engage in a simple reading and discussion lesson with students. The text itself is not very long or difficult, especially for middle school students. The teacher can take the direct approach and read portions of the text to the students while calling on students to volunteer to read other sections; this should take only one to two classes to accomplish. Alternatively, for a constructivist approach, students could be split into groups and take turns reading the text and engaging with it as much as possible within the group. Regardless of the method, students can write down observations and questions while going through the reading; you might start a discussion before the next reading to talk about these. If they are reading in groups, students can take turns talking about what they noticed and answering questions from other students. Applicable to all aforementioned grade levels.

- Photography/Imagination Project: Like the protagonists of Onibi, students can go out with a camera and take photos of natural landscapes or particular monuments they come across in their own neighborhoods. They could then print photos that catch their attention and develop stories about the supernatural creatures they believe could be lurking in that area. They could also associate a place in their photos with a well-known supernatural creature, or they can make up their own. Either way, the student should draw a picture of the creature they were imagining along with a description of its characteristics on a separate sheet of paper. The teacher could hang these in the classroom and have the students take notes about the supernatural creatures that could live in the places within the photos. Applicable to all aforementioned grade levels.

- Yōkai Poster Project: A poster project is another straightforward idea to build upon the ideas, concepts, and folklore learned through Onibi. The teacher can decide whether the students work in groups or individually. If in groups, it may be best to focus only on yōkai featured in Onibi. If the students work individually, it may be preferable to use Yokai Attack! and Yurei Attack!, both written by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, as supplementary materials so each student can choose a unique spirit or monster (these texts are explained below). Once students have added text and images to their posters, presentations can be done by each group or individual student.

Common Core Standards

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.1. Ask and answer such questions as who, what, where, when, why, and how to demonstrate understanding of key details in a text.

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.RL.2.2. Recount stories, including fables and folktales from diverse cultures, and determine their central message, lesson, or moral.

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.1. Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.

Literature and Media Connections

The supplementary texts that can be employed to help enrich the new ideas and concepts being learned through Onibi vary by grade level. Teachers may wish to do some preparatory reading ahead of teaching this book, using some of the recommended texts below.

Elementary Texts: NonNonBa by Shigeru Mizuki (translated by Jocelyne Allen, Drawn and Quarterly, 2012); Gegege no Kitaro by Shigeru Mizuki (various collected editions).

Onibi provides a basic introduction to concepts of the supernatural as they appear in Japanese folklore and mythology. Texts such as the manga written and illustrated by Shigeru Mizuki can be used to reinforce what students learn from Onibi. Mizuki was a manga artist throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and his work is still featured in the media today. His most popular serialized work, Gegege no Kitaro, follows the exploits of the friendly yōkai Kitaro as he does his best to help the human and spirit worlds find balance. Many of Kitaro’s friends are themselves yōkai and yūrei, but while many of his friends find it fun to scare humans, Kitaro himself is not in the business of frightening or harming humans. Rather, he teaches both sides how to better themselves.

Fascinated by the supernatural and worldwide mythology, Mizuki went on to write a more serious retelling of his childhood from the perspective of interacting with the spirit world in myriad ways. The resulting manga book, NonNonBa, is a tale of his relationship with an elderly woman in his village, who introduces him to all the monsters and myths of the local area. These tales eventually take Mizuki’s younger self on a journey during which he learns about his relationship to the wider world and how to appreciate the bonds and friendships he makes as he grows older.

Both books are appropriate for younger readers and will increase their cultural knowledge about Japan. The stories are told in an easily accessible format that builds on what was introduced through Onibi.

Middle School Texts: Yokai Attack!: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, illustrated by Tatsuya Morino (Tuttle Publishing, 2012). Yurei Attack!: The Japanese Ghost Survival Guide by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, illustrated by Shinkichi (Tuttle Publishing, 2012).

Both Yokai Attack! and Yurei Attack! are straightforward and vibrant in ways that will hold middle school students’ attention as they read the brief descriptions and examples of each yōkai and yūrei. Presented in the form of field guides, with color illustrations for each monster, these books by Yoda and Alt are a great way for students with higher reading abilities and a penchant for longer descriptions and definitions to learn more about the supernatural and mythological figures that appear only briefly in Onibi. These texts are also solid to use along with project ideas for students, for example, when assigning research on a particular yōkai or yūreithat could then be shared with fellow students through an interactive and engaging poster project.

Elementary and Middle School Media: Spirited Away (2001) directed by Hayao Miyazaki, and Pom Poko(1994) directed by Isao Takahata.

Another avenue for increasing student engagement and understanding of these ideas is the use of film. Anime is a visual medium used for a lot of movies and television shows in Japan, especially those aimed at children and teenagers. Of the anime studios in Japan, Studio Ghibli is usually considered among the most masterful at using the medium to tell profound stories. Spirited Away and Pom Poko focus heavily on the supernatural. The former is the tale of a girl lost in the spirit world who befriends all sorts of unique characters on her journey to return to the human world. The latter depicts how particular shape-shifting nature spirits—the raccoon dogs known as tanuki—respond to the encroachment of urbanization on their natural habitat in the real world. Both are engrossing stories with varied characters and messages about a person’s relationship with the world around them, seen and unseen, and both are great ways to show, rather than tell, students more about the ideas and concepts introduced in Onibi. Great resources to approach different cultural values and stories, these films can be used to bookend a unit on Japan concerning myths and folklore and to transition into other aspects, like life in modern Japan or Japanese cities. No matter how the teacher uses these films, they are both highly regarded, ideal for quickly teaching cultural lessons that students may not otherwise fully understand.

High School Text: A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine by John K. Nelson (University of Washington Press, 1996).

A scholarly text, this book is written at a level most older high school students will understand and provides a thorough anthropological picture of the interplay between Japanese society and spirituality that students might not otherwise have the opportunity to learn about. During his time teaching in Japan, Nelson visited the Suwa Shrine in Nagasaki, befriending the head priest and learning the intricacies of the temple’s day-to-day operations and how the rituals and worship related to the larger community it served. Nelson is thorough in his analysis and explanations, covering history, concepts, mythology, first-hand observations, community life, and personal stories that are all important in weaving a complete picture of not only Suwa Shrine but also the vital indigenous spiritual history of Japan. Nelson’s text is indispensable for any educator looking to expand their knowledge on the topic of Japanese spirituality and religion, and it serves as a decent introduction to an aspect of Japanese culture that is not often discussed. A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine could be split up to provide case studies of certain aspects of Japanese spirituality and folklore that are only hinted at in Onibi, or it could help guide the pattern of a particular lesson and the information the teacher wishes to impart. No matter how the text is used in the classroom—either as supplementary material, to fill in informational blanks, or for reading and discussion material—A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine will enrich the student’s understanding of Japanese spirituality as a lived experience.

Common Core Standards

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.W.2.2. Write informative/explanatory texts in which they introduce a topic, use facts and definitions to develop points, and provide a concluding statement or section.

CCSS. ELA-LITERACY.W.2.7. Participate in shared research and writing projects (for example, read a number of books on a single topic to produce a report; record science observations).

Author: Matthew Kizior, Career Readiness Teacher 2021

Winner 2018 Japan International Manga Award