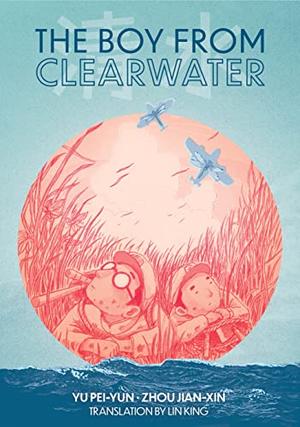

The Boy from Clearwater: Book 1

(Levine Querido)

- Non-fiction

- Set in Taiwan

Key words: Contemporary, biography, human rights, translation

Taiwan, 1930s.

Tsai Kun-lin, an ordinary boy, was born in Qingshui. He grew up happily sneaking into the sugar cane fields reciting nursery rhymes he couldn’t understand, despite Japanese occupation looming over him. As war emerges, Tsai’s memories shift to military parades, air raids, and watching others face conscription into the army. After the war comes a new era under the rule of the Chinese National Party, and the book-loving teenager tries hard to learn Mandarin and be a good son. He believes he is finally stepping towards a comfortable future, but little does he know, a dark cloud awaits him ahead.

Taiwan, 1950s.

In his second year at Taichung First Senior High School, Tsai had attended a book club hosted by his teacher. This comes back to haunt him when he is consequently arrested on a charge of taking part in an “illegal” assembly. After being tortured into a false confession, he is sentenced to ten years in prison and eventually sent to Green Island for “reformation.” Lasting until his release in September 1960, Tsai, a victim of the White Terror era, spent ten years of his youth in prison, experiencing unspeakable horrors as well as unimaginable kindnesses. But he is now ready to embrace freedom.

For fans of Persepolis and March comes an incredible true story that lays bare the tortured and triumphant history of Taiwan, an island claimed and fought over by many countries, through the life story of a man who lived through its most turbulent times.

Taiwan’s modern history is a complex narrative of colonization, resistance, economic transformation, and eventual democratization. From the establishment of Japanese colonial rule in 1895 to the authoritarian grip of the Kuomintang (KMT) government and the transformative period of the Taiwan Miracle, the island’s journey has been shaped by both external influences and internal resilience. The true story of Kun-lin Tsai, as portrayed in The Boy from Clearwater, highlights many of these themes.

Following the Sino-Japanese War, Taiwan became the first colony in Japan’s burgeoning empire. The colonial administration developed infrastructure, including railways, ports, and sanitation systems, and introduced public education. However, these advancements primarily benefited the Japanese imperial economy, colonial settlers in Taiwan, and elite collaborators rather than the general population.

During the 1930s, Japan’s militarization intensified, and so did its assimilation policies. Taiwanese were encouraged—and later forced—to adopt Japanese names, speak Japanese, and follow Shinto practices. This period saw the suppression of traditional Chinese culture and languages, creating a deep cultural divide that lingered for decades. Resistance against these policies varied, from covert cultural preservation efforts to outright rebellions.[1]

Economically, Taiwan became an important supplier of agricultural products and raw materials for Japan’s expanding empire. Sugar production, in particular, grew significantly under Japanese oversight, with plantations and processing plants dotting the island. While these developments boosted Taiwan’s economic output, they were primarily designed to serve Japanese interests, leaving many Taiwanese in poverty and subservience.

In 1937, Japan invaded the Republic of China and quickly overran Nanjing, the capital. Four years later, in 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and expanded its empire throughout Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. During the war, Taiwan served as both a military base and a supply hub for Japan’s expansionist campaigns in the Pacific. The island’s infrastructure, including ports, railways, and airfields, was heavily utilized for military purposes, and its agricultural output—particularly sugar and rice—supported Japan’s war effort. Taiwanese men were conscripted into the Japanese army, with many serving in various capacities across Asia. Kun-lin Tsai and his family were no exceptions. Additionally, the local population endured strict wartime policies, including food rationing and intensified assimilation efforts that demanded unwavering loyalty to Japan. Bombing raids by Allied forces targeted key facilities, causing significant civilian casualties and destruction. By the war’s end in 1945, Taiwan’s economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged, setting the stage for a challenging postwar transition as the island was transferred from Japanese to Chinese Nationalist rule.

The initial postwar optimism among Taiwan’s residents quickly turned into disillusionment as the KMT government, led by Chiang Kai-shek, imposed corrupt and exploitative policies. Economic mismanagement and rising inflation fueled widespread dissatisfaction.

On February 28, 1947, KMT officers harassed a street vendor for selling contraband cigarettes. The incident quickly turned violent, leading to island-wide protests. The KMT’s response was brutal, with military forces massacring tens of thousands of Taiwanese in what became known as the 2-28 Incident. Eyewitness accounts detail horrific scenes of soldiers firing into crowds, arbitrary arrests, and mass executions.

In 1949, Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT government was defeated by Mao Zedong and his Communist Party on the Chinese mainland. Chiang and approximately 1.5 million Chinese refugees fled to Taiwan, further complicating the island’s ethnic dynamics.

These newcomers, known as “mainlanders” (waishengren 外省人; pronounced: WHY-sheng-ren), set up the rump Republic of China in exile and held privileged positions in the government and military, while native Taiwanese (benshengren 本省人; pronounced: BEN-SHENG-ren) were marginalized. Mainlanders brought with them a sense of superiority, viewing themselves as the legitimate rulers of China and Taiwan, and seeing the Taiwanese as Japanese collaborators. Meanwhile, native Taiwanese, who had experienced fifty years of Japanese colonial rule, found themselves excluded from key positions of power. Policies favoring mainlanders, such as better access to jobs and education, deepened the divide. Not surprisingly, these actions created an “us versus them” dynamic.

The 2-28 Incident and the fall of the KMT regime on the mainland resulted in what came to be called the White Terror, a period of political repression targeting anyone perceived to be in opposition to the KMT. For the next three decades, martial law was imposed, and freedom of speech was severely curtailed. Thousands of people were imprisoned, tortured, or executed, often on dubious charges of being “communist sympathizers.” Families of the accused faced social ostracism and economic hardships, creating a pervasive atmosphere of fear. Despite these challenges, underground resistance movements and advocacy groups began to form, laying the groundwork for Taiwan’s eventual democratization. This divide created lasting resentments and tensions that shaped Taiwan’s politics and society for decades, right up to the present day.

Green Island, located off Taiwan’s eastern coast, became infamous as a detention center for political prisoners during the White Terror. From the 1950s to the 1980s, thousands of individuals accused of being “communist sympathizers” or “subversives” were sent to this remote prison, including Kun-lin Tsai. The harsh conditions and forced ideological re-education programs symbolized the KMT’s authoritarian grip on the island.

Prisoners on Green Island endured extreme physical and psychological hardships. They were subjected to grueling labor, poor living conditions, and constant surveillance. The prison also hosted indoctrination programs designed to instill loyalty to the KMT. Despite these efforts, many detainees found ways to resist, sharing banned literature, composing secret writings, and forming solidarity networks.

In addition to the White Terror, the KMT’s imposition of Mandarin as the official language exacerbated tensions. Taiwanese and Japanese, widely spoken by the native population, were relegated to informal contexts, fostering a sense of cultural erasure among Taiwanese people. Public schools mandated the use of Mandarin, and speaking Taiwanese or Japanese in official settings often resulted in censure or punishment.

This multilingual environment created unique challenges and opportunities. Literature and popular culture often blended languages, reflecting the island’s complex identity. For example, songs in Taiwanese became a vehicle for expressing local sentiments, while Japanese anime and manga influenced young readers. Meanwhile, Mandarin gradually became the dominant language in urban areas and professional contexts, creating generational divides in linguistic preferences.

During the KMT-dominated era in Taiwan, manhua (comics) played a crucial role in reflecting and shaping the sociopolitical landscape. Despite strict censorship and the imposition of the Comic Code, which regulated content to ensure it aligned with government ideals, manhua provided a unique medium for subtle social commentary and cultural expression. Artists like Liu Hsing-chin used their work to address issues such as urban-rural divides and the rapid industrialization of Taiwan.[2] Manhua also served as a form of escapism and entertainment for the public, offering a creative outlet during a time of political repression. Following his release from Green Island, Kun-lin Tsai eventually became a major leader in the manhua movement. This period laid the groundwork for the vibrant and diverse comic culture that Taiwan enjoys today.

Despite its political turmoil, Taiwan experienced extraordinary economic growth between the 1950s and 1980s, often referred to as the “Taiwan Miracle.” Initially reliant on U.S. aid, Taiwan shifted to export-oriented industrialization under the guidance of the KMT government. Industries such as textiles, electronics, and petrochemicals flourished, turning Taiwan into one of Asia’s “Four Tigers.”

Land reforms in the 1950s, which redistributed land from landlords to tenant farmers, boosted agricultural productivity and provided the capital for industrialization. The government also invested heavily in education and infrastructure, creating a skilled workforce and modern facilities. By the 1980s, Taiwan had transformed into a global manufacturing hub and a model of economic development.

This economic growth also had profound social impacts. Urbanization accelerated as people moved from rural areas to cities for job opportunities. The rise of a middle class empowered citizens to demand greater political rights and freedoms, contributing to Taiwan’s democratization. By the late 1980s, Taiwan’s economy was not only thriving but also driving social and political change, setting the stage for the democratic reforms of the 1990s.

Martial law in Taiwan, which lasted for over thirty-eight years, was lifted on July 15, 1987, by President Chiang Ching-kuo.[3] This marked the end of a period characterized by strict government control, suppression of dissent, and limited civil liberties. The lifting of martial law was a significant step toward democratization, allowing for greater political freedom and the eventual establishment of a multi-party democratic system. This transition was part of a broader wave of democratization occurring globally at the end of the Cold War.

The stories of Green Island survivors, including Kun-lin Tsai’s, played a crucial role in Taiwan’s democratization and reconciliation processes. These personal and collective recollections have helped to highlight the injustices and human rights abuses that occurred under martial law, fostering a broader public awareness and acknowledgment of this dark chapter in Taiwan’s history.[4] The transformation of Green Island into a Human Rights Cultural Park serves as a poignant reminder of past atrocities and a symbol of the commitment to human rights and democratic values.[5] By confronting and commemorating these painful memories, Taiwan has been able to promote healing and reconciliation, paving the way for a more open and democratic society.

Taiwan’s history is a rich tapestry of colonization, resistance, economic transformation, and democratization. From Japanese colonial rule and its assimilation policies to the KMT’s authoritarian regime and eventual democratization, these experiences have profoundly shaped Taiwan’s identity. The stories of Green Island survivors, the cultural resilience expressed through manhua, and the economic achievements of the Taiwan Miracle highlight the island’s journey toward reconciliation and progress. The story of Kun-lin Tsai, in The Boy from Clearwater, is one example of Taiwan’s ability to confront its past and embrace its diverse heritage. It serves as a powerful example of resilience and the pursuit of democratic ideals.

Author: David Kenley, PhD, modern China specialist

2025

[1] For example, the Wushe Incident—a major uprising against Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan—occurred in October 1930, led by members of the Seediq indigenous group. One of the most significant episodes of resistance during Japan’s fifty-year occupation of Taiwan (1895–1945), it resulted in increased efforts to assimilate the people of Taiwan.

[2] Julia Chen, “Tales of Taiwan’s Comic Artists: Persecution, Isolation and Endless Talent,” The News Lens, 25 January 2018. Available online at https://international.thenewslens.com/article/88234

[3] Mark Harrison, “The End of Martial Law: An Important Anniversary for Taiwan,” Global Taiwan Institute, 26 July 2017. Available online at https://globaltaiwan.org/2017/07/the-end-of-martial-law-an-important-anniversary-for-taiwan/

[4] Lung-chih Chang, “Island of Memories. Postcolonial Historiography and Public Discourse in Contemporary Taiwan,” International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity, 2014.

[5] Guy Beauregard, “‘There but Not There’: Green Island and the Transpacific Dimensions of Representing White Terror,” MELUS, 48.3 (Fall 2023): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/melus/mlad064

The Boy from Clearwater offers educators and students an opportunity to explore pivotal eras in Taiwanese history and to identify and discuss themes that will resonate with young readers in grades 9–12. The graphic novel style invites readers into the world of protagonist Kun-lin Tsai with its simple and direct text, engaging illustrations, and riveting plot.

The Boy from Clearwater was published in 2023[1] by the author Pei-Yun Yu, with illustrations by Jian-Xin Zhou. It depicts one of the most consequential eras of Taiwan’s history: the period of martial law known as the “White Terror,” which lasted from 1947 to 1987. The novel chronicles the tragedies and triumphs of Kun-lin Tsai, whose life followed the arc of this tumultuous time in Taiwan’s history.

Kun-lin Tsai was just a boy when the island of Taiwan, colonized by Japan in 1895, was drawn into the shadows of World War II. Kun-lin is drafted by the Japanese as a student soldier in 1945, near the end of the war. In 1949, Taiwan was brought under Republic of China (ROC) rule when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang (KMT) army fled the mainland after being defeated in the Chinese Civil War. In 1950 Kun-lin is arrested for treason, for the crime of joining his high school book club. He is imprisoned for a decade and “re-educated” on Green Island (about 20 miles off the eastern coast of Taiwan).

Author Pei-Yun Yu and the book’s translator, Lin King, communicate the vacillation of control over Taiwan using color-coded text throughout the novel’s two books: green for Japanese (the narrative that takes place when Japan ruled Taiwan); red for Mandarin (the narrative that takes place under ROC rule in Taiwan); and blue for Taiwanese (used by Kun-lin Tsai when he speaks with friends and family in personal and informal settings).

What grade levels or student populations are best served with the book?

We recommend this book for high school (grades 9–12), in both English Language Arts and Social Studies. While some of the illustrations depicting Kun-lin’s torture and imprisonment by military police might warrant a content warning, the book’s narrative is not graphic, and neither are most images. It should also be mentioned that Kun-lin’s father takes his own life while Kun-lin is detained on Green Island, and students should be warned about this in advance as well. Overall, the narrative addresses mature topics, but the plot is a coming-of-age narrative, and the reading level is appropriate for students in grades 9–12.

Additionally, schools that offer Japanese and Chinese language programs may be able to create cross-curricular units for their students in ELA, Social Studies, and World Language classes since the books so richly shares these languages throughout their entirety along with the English translation.

Connections to English Language Arts:

For teachers of English Language Arts (ELA), this graphic novel offers a sobering window into a dark chapter of one society’s past and can be compared and contrasted with novels that also address its themes of “loss of innocence,” “marginalization,” “identity,” “coming-of-age,” “political oppression,” and “hope,” such as They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.

Because The Boy from Clearwater’s protagonist faces hardships and privations that rob him of his youth and innocence, such as war, physical punishment, and incarceration, young adult readers may be particularly drawn into his story and may find that the book’s themes resonate with many of their concerns as teenagers.

Connections to Social Studies:

Teachers of Social Studies might use this book to discuss important events and eras in World History and U.S. History courses. Pivotal events in China and Taiwan’s histories intersect with terms such as the Republic of China, World War II, the Chinese Civil War, China’s Communist Revolution, the People’s Republic of China, the Cold War, the White Terror, the Korean War, Taiwan’s democratization, and South China Sea tensions. Similarly, Japan’s imperialist and colonist history plays an important role in this book with contextualizing events such as the Meiji Restoration, the Mudan Incident, the Taiwan Expedition, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, and the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ceded the island of Taiwan to Japan from Qing-dynasty China in 1895 as a result of China’s loss to Japan in the Sino-Japanese War.

Ideas for Classroom Use:

- Unpack the illustrations. The illustrations throughout the novel are so powerful and descriptive that a thematic collection of them could, with just a few accompanying questions, serve as an assessment tool for a lesson plan focused on any of the topics above.

- Discuss censorship. The protagonist Kun-lin Tsai was arrested on charges of treason for joining a high school book club—deemed “an illegal organization” by the KMT government in Taiwan. Is censorship still an issue today? If so, what kinds of issues fuel the phenomenon of censorship?

- Political oppression as an historical phenomenon. Consider assigning students (or allowing them to select on their own with teacher approval) one historical example of political oppression that they will then compare and contrast with Taiwan’s “White Terror” era of martial law and Kun-lin Tsai’s struggle. Suggestions include the following: the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Apartheid in South Africa, the Holocaust, and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Students could research the “White Terror” in Taiwan and one of the other historical examples and write an essay or present a slide deck about their research.

Author: Catherine Fratto, Global Studies Center, University of Pittsburgh

2025

[1] Book 2 of The Boy from Clearwater, published in 2024 and also a Freeman Book Award winner, details Kun-lin Tsai’s life upon his release from prison in 1960 and his efforts to rebuild his life in the aftermath of Taiwan’s “White Terror” period.