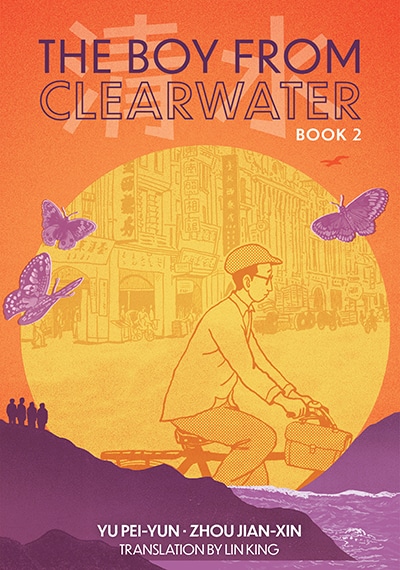

The Boy from Clearwater: Book 2

(Levine Querido)

- Non-fiction

- Set in Taiwan

Key words: Contemporary, biography, human rights, translation

After his imprisonment in Green Island, Kun-lin struggles to pick up where he left off ten years earlier. He reconnects with his childhood crush Kimiko and finds work as an editor, jumping from publisher to publisher until finally settling at an advertising company. But when manhua publishing becomes victim to censorship, and many of his friends lose their jobs, Kun-lin takes matters into his own hands. He starts a children’s magazine, Prince, for a group of unemployed artists and his old inmates who cannot find work anywhere else. Kun-lin’s life finally seems to be looking up… but how long will this last?

Forty years later, Kun-lin serves as a volunteer at the White Terror Memorial Park, promoting human rights education. There, he meets Yu Pei-Yun, a young college professor who provides him with an opportunity to reminisce on his past and how he picked himself up after grappling with bankruptcy and depression. With the end of martial law, Kun-lin and other former New-Lifers felt compelled to mobilize to rehabilitate fellow White Terror victims, forcing him to face his past head-on. While navigating his changing homeland, he must conciliate all parts of himself – the victim and the savior, the patriot and the rebel, a father to the future generation and a son to the old Taiwan – before he can bury the ghosts of his past.

Taiwan’s modern history is a complex narrative of colonization, resistance, economic transformation, and eventual democratization. From the establishment of Japanese colonial rule in 1895 to the authoritarian grip of the Kuomintang (KMT) government and the transformative period of the Taiwan Miracle, the island’s journey has been shaped by both external influences and internal resilience. The true story of Kun-lin Tsai, as portrayed in The Boy from Clearwater, highlights many of these themes.

Following the Sino-Japanese War of 1895, Taiwan became the first colony of Japan’s burgeoning empire. The colonial administration developed railways, ports, sanitation systems, and public schools. However, these advancements primarily benefited the Japanese imperial economy, colonial settlers in Taiwan, and elite collaborators rather than the general Taiwanese population.

During the 1930s, Japan’s rulers pushed aggressive assimilation policies on their colonies. Taiwanese were encouraged—and later forced—to adopt Japanese names, speak Japanese, and follow Shinto practices. This period saw the suppression of traditional Chinese culture and languages, creating a deep cultural divide that lingered for decades. Resistance against these policies varied, from covert cultural preservation efforts to outright rebellions.[1]

Economically, Taiwan became an important supplier of agricultural products and raw materials for Japan’s expanding empire. Sugar production, in particular, grew significantly under Japanese oversight, with plantations and processing plants dotting the island. While these developments boosted Taiwan’s economic output, they were primarily designed to serve Japanese interests, leaving many Taiwanese in poverty and subservience.

In 1937, Japan invaded the Republic of China and quickly overran its Nanjing capital. Four years later, in 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and expanded its empire throughout Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. During the war, Taiwan served as both a base and a supply hub for Japan’s military campaigns in the Pacific. The island’s infrastructure, including ports, railways, and airfields, was heavily utilized for military purposes, and its agricultural output—particularly sugar and rice—supported Japan’s war effort. Taiwanese men were conscripted into the Japanese army, with many serving in various capacities across Asia. Kun-lin Tsai and his family members were no exceptions. Additionally, the local population endured strict wartime policies, including food rationing and demands for unwavering loyalty to Japan. Bombing raids by Allied forces targeted key facilities, causing significant civilian casualties and destruction. By the war’s end in 1945, Taiwan’s economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged, setting the stage for a challenging postwar transition as the island transferred from Japanese to Chinese KMT rule.

Despite initial postwar optimism among Taiwan’s residents, disillusionment quickly spread as the new government imposed corrupt and exploitative policies. Economic mismanagement and rising inflation fueled widespread dissatisfaction. On February 28, 1947, KMT officers harassed a street vendor for selling contraband cigarettes. The incident quickly turned violent, leading to island-wide protests. The KMT’s response was brutal, with military forces massacring tens of thousands of Taiwanese in what became known as the 228 incident (also known as the February 28 massacre). Eyewitness accounts detail horrific scenes of soldiers firing into crowds, arbitrary arrests, and mass executions.

In 1949, Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT government was defeated by Mao Zedong and his Communist Party on the Chinese mainland. Chiang and approximately 1.5 million Chinese refugees fled to Taiwan, further complicating the island’s ethnic dynamics. These newcomers, known as “mainlanders” (waishengren or 外省人; pronounced: WHY-sheng-ren), set up the Republic of China government in exile and held privileged positions in the government and military, while native Taiwanese (benshengren or本省人; pronounced: BEN-SHENG-ren) were marginalized. Mainlanders brought with them a sense of superiority, viewing themselves as the legitimate rulers of China and Taiwan, and seeing the Taiwanese as Japanese collaborators. Meanwhile, native Taiwanese, who had experienced fifty years of Japanese colonial rule, found themselves excluded from key positions of power. Policies favoring mainlanders, such as better access to jobs and education, deepened the divide. Not surprisingly, these actions created an “us versus them” dynamic.

The 228 incident and the fall of the KMT regime on the mainland resulted in what came to be called the White Terror, a period of political repression targeting anyone perceived to be in opposition to the KMT. For the next three decades, martial law was imposed, and freedom of speech was severely curtailed. Government officials imprisoned, tortured, and executed thousands of civilians, often on unproven charges of being “communist sympathizers.” In the pervasive atmosphere of fear, families of the accused faced social ostracism and economic hardships. Despite these challenges, underground resistance movements and advocacy groups began to form, laying the groundwork for Taiwan’s eventual democratization. This divide created lasting resentments and tensions that shaped Taiwan’s politics and society for decades, right up to the present day.

Green Island, located off Taiwan’s eastern coast, became infamous as a detention center for political prisoners during the White Terror. From the 1950s to the 1980s, thousands of “subversives” were sent to this remote prison, including Kun-lin Tsai. The harsh conditions and forced ideological re-education programs symbolized the KMT’s authoritarian grip on the island. Prisoners on Green Island endured extreme physical and psychological hardships. They were subjected to grueling labor, poor living conditions, and constant surveillance. The prison also hosted indoctrination programs designed to instill loyalty to the KMT. Despite these efforts, many detainees found ways to resist, sharing banned literature, composing secret writings, and forming solidarity networks.

In addition to the White Terror, the KMT’s imposition of Mandarin as the official language exacerbated tensions. Taiwanese and Japanese, widely spoken by the native population, were relegated to informal contexts, fostering a sense of cultural erasure among Taiwanese people. Public schools mandated the use of Mandarin, and speaking Taiwanese or Japanese in official settings often resulted in punishment.

This multilingual environment created unique challenges and opportunities. Literature and popular culture often blended languages, reflecting the island’s complex identity. For example, songs in Taiwanese became a vehicle for expressing local sentiments, while Japanese anime and manga influenced young readers. Meanwhile, Mandarin gradually became the dominant language in urban areas and professional contexts, creating generational divides in linguistic preferences.

During the KMT-dominated era in Taiwan, manhua (comics) played a crucial role in both reflecting and shaping the sociopolitical landscape. Despite strict censorship and the imposition of the Comic Code, which regulated content to ensure it aligned with government ideals, manhua provided a unique medium for subtle social commentary and cultural expression. Artists like Hsing-chin Liu used their work to address issues such as urban-rural divides and the rapid industrialization of Taiwan.[2] Manhua also served as a form of escapism and entertainment for the public, offering a creative outlet during a time of political repression. Following his release from Green Island, Kun-lin Tsai eventually became a major leader in the manhua movement. This period laid the groundwork for the vibrant and diverse comic culture that Taiwan enjoys today.

Despite its political turmoil, Taiwan experienced extraordinary economic growth between the 1950s and 1980s, often referred to as the “Taiwan Miracle.” Initially reliant on U.S. aid, Taiwan shifted to export-oriented industrialization under the guidance of the KMT government. Industries such as textiles, electronics, and petrochemicals flourished, turning Taiwan into one of Asia’s “Four Tigers.” Land reforms in the 1950s, which redistributed land from landlords to tenant farmers, boosted agricultural productivity and provided the capital for industrialization. The government also invested heavily in education and infrastructure, creating a skilled workforce and modern facilities. By the 1980s, Taiwan had transformed into a global manufacturing hub and a model of economic development.

This economic growth had profound social and political impacts. Urbanization accelerated as people moved from rural areas to cities for job opportunities. The rise of a middle class empowered citizens to demand greater political rights and freedoms. In 1987, President Chiang Ching-kuo announced the end of Taiwan’s thirty-eight years of martial law.[3] Thus ended the era of strict government control, suppression of dissent, and limited civil liberties. This transition was part of a broader wave of democratization occurring globally at the end of the Cold War.

The stories of Green Island survivors, including Kun-lin Tsai’s, played a crucial role in Taiwan’s democratization and reconciliation processes. These personal and collective recollections have helped to highlight the injustices and human rights abuses that occurred under martial law, fostering a broader public awareness and acknowledgment of this dark chapter in Taiwan’s history.[4] The transformation of Green Island into a Human Rights Cultural Park serves as a poignant reminder of past atrocities and a symbol of the commitment to human rights and democratic values.[5] By confronting and commemorating these painful memories, Taiwan has been able to promote healing and reconciliation, paving the way for a more open and democratic society.

Taiwan’s history is a rich tapestry of colonization, resistance, economic transformation, and democratization. From Japanese colonial rule and its assimilation policies to the KMT’s authoritarian regime and eventual democratization, these experiences have profoundly shaped Taiwan’s identity. The stories of Green Island survivors, the cultural resilience expressed through manhua, and the economic achievements of the Taiwan Miracle highlight the island’s journey toward reconciliation and progress. Kun-lin Tsai, the boy from Clearwater, is one example of Taiwan’s ability to confront its past and embrace its diverse heritage.

Author: David Kenley, PhD, Professor of History and Cyber Leadership, Dakota State University 2025

[1] For example, the Wushe Incident—a major uprising of the Seediq indigenous people against Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan—occurred in October 1930 in the village of Wushe. One of the most significant episodes of resistance during Japan’s fifty-year occupation of Taiwan (1895–1945), the uprising was brutally suppressed and led to increased efforts to assimilate the people of Taiwan.

[2] Julia Chen, “Tales of Taiwan’s Comic Artists: Persecution, Isolation, and Endless Talent,” The News Lens, 25 January 2018. Available online at https://international.thenewslens.com/article/88234.

[3] Chiang Ching-kuo was the son of Chiang Kai-shek, and he assumed leadership of the party and the country upon his father’s death in 1975.

[4] Lung-chih Chang, “Island of Memories. Postcolonial Historiography and Public Discourse in Contemporary Taiwan,” International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 2 (March 2014), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.18352/hcm.471.

[5] Guy Beauregard, “There but Not There: Green Island and the Transpacific Dimensions of Representing White Terror,” MELUS, 48.3 (Fall 2023): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/melus/mlad064.

The Boy from Clearwater, Book 2, a YA (Young Adult) graphic novel, offers an opportunity for educators and students to explore several pivotal historical eras in Taiwanese history and to identify and discuss themes spanning a range of 9–12 grade disciplines that will resonate with young readers. The graphic novel genre invites readers into the world of protagonist Kun-lin Tsai with its simple and direct text, its engaging illustrations, and its riveting plot.

The Boy from Clearwater was published in 2023* by the author Yu Pei-Yun with illustrations by Zhou Jian-Xin. (Yu, Zhou, and Tsai are all family names; family names are given first in East Asian cultures.) This graphic novel depicts one of the most consequential eras of Taiwan’s history: the nearly half-century long “White Terror” period of martial law on the island, from 1947–1987. The novel chronicles the tragedies and triumphs of protagonist, Kun-lin Tsai, whose life followed the arc of this tumultuous time in Taiwan’s history. Kun-lin Tsai was just a boy when the island of Taiwan, colonized by Japan in 1895, was drawn into the shadows of World War II. Kun-lin is drafted as a student soldier near the war’s end in 1945 and then brought under Republic of China (ROC) rule when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang (KMT) army flee mainland China in 1949 upon their defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Kun-lin Tsai is the victim of Taiwan’s Cold War anti-communist military persecution when he is arrested for treason, imprisoned, and “re-educated” on Green Island (about twenty miles off the eastern coast of Taiwan) for a decade in 1950 for the crime of joining his high school’s book club.

In The Boy from Clearwater, Book 2, Kun-lin Tsai returns to his home in Taipei, Taiwan, after serving his ten-year prison term, but struggles to adapt to life back home, learning that his father took his own life while Kun-lin was in prison and feeling as though his own life has passed him by while he was imprisoned. Happily, however, Kun-lin is reunited with his childhood sweetheart, Pik-Ju Lunn, or “Kimiko” (her Japanese name), and the two are married in 1962. Kun-lin goes through a dizzying array of jobs over the next decades, from potential teacher (his application is denied due to his “criminal past”) to children’s magazine editor to corporate employee, all the while dodging his past. In 2018, Kun-lin Tsai meets the future author of The Boy from Clearwater, Pei-Yun Yu, at the National Human Rights Museum’s exhibition “Delayed with Love: Last Letters from Victims of White Terror Era Political Persecution,” where he shared his experiences as a political prisoner on Green Island. Pei-Yun Yu went on to conduct a series of interview sessions to collect Kun-lin Tsai’s oral history and to ultimately share his remarkable life in graphic novel form. As a fitting ending to Kun-lin Tsai’s story, the last page of the book announces Kun-lin’s exoneration for his political crimes during the White Terror by Taiwan’s Transitional Justice Commission in 2018.

Author Pei-Yun Yu and the book’s translator, Lin King, communicate the vacillation between control of Taiwan using color-coded text throughout the novel’s two books: green for Japanese language (the narrative that takes place when Japan ruled Taiwan); red for Mandarin (the narrative that takes place under ROC rule in Taiwan); and blue for Taiwanese (used by Kun-lin Tsai when he is speaking with friends and family in personal and informal settings in the book).

*Book 2 of The Boy from Clearwater, published in 2024, details Kun-lin Tsai’s life upon his release from prison in 1960 and his efforts to rebuild his life in the aftermath of Taiwan’s “White Terror” period.

What grade levels or student populations are best served with the book?

Our recommendation to educators is high school (9–12 grade) English Language Arts (ELA) and Social Studies. While some of the illustrations that depict the protagonist Kun-lin Tsai’s torture and imprisonment by military police might warrant a content warning before students view them, the narrative of the book is not graphic, and neither are most images. It should also be mentioned that Kun-lin Tsai’s father takes his own life while Kun-lin is detained on Green Island, and students should receive a content warning about this as well. Overall, while the narrative addresses mature topics, the plot is in keeping with a coming-of-age narrative and the reading level is appropriate for 9–12 graders.

Additionally, schools that offer Japanese and Chinese language programs may be able to create cross-curricular units for their students in ELA, Social Studies, and these World Language classes since Book 1 and Book 2 so richly share these languages throughout their entirety along with the English translations.

Connections to English Language Arts:

For teachers of ELA, this graphic novel offers a sobering window into a dark chapter of one society’s past and can be compared and contrasted with novels that also address its themes of loss of innocence, marginalization, identity, coming-of-age, political oppression, and hope. These include They Called Us Enemyby George Takei, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.

Because The Boy from Clearwater’s protagonist faces hardships and privations that rob him of his youth and innocence, such as war, physical punishment, and incarceration, young adult readers may be particularly drawn into his story and may find that the book’s themes resonate with many of their concerns as teenagers.

Connections to Social Studies:

Teachers of Social Studies might use this book to discuss important historical events and eras in World History and U.S. History courses. Pivotal events in China and Taiwan’s histories intersect with terms such as the Republic of China, World War II, the Chinese Civil War, China’s Communist Revolution, the People’s Republic of China, the Cold War, the White Terror, the Korean War, Taiwan’s democratization, the Taiwan Miracle, and South China Sea tensions. Similarly, Japan’s imperialist and colonial history plays an important role in this book with contextualizing events such as the Meiji Restoration, the Mudan Incident, the Taiwan Expedition, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, and the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ceded the island of Taiwan to Japan from Qing dynasty China in 1895 as a result of China’s loss to Japan in the Sino-Japanese War.

Ideas for Classroom Use:

- Unpack the message behind the illustrations. The illustrations throughout the novel are so powerful and descriptive that a thematic collection of them could, with just a few accompanying questions, serve as an assessment tool for a lesson plan focused on any of the topics above.

- Discuss censorship. The protagonist Kun-lin Tsai was arrested on charges of treason for joining a high school book club—deemed “an illegal organization” by the KMT government in Taiwan. Is censorship still an issue today? If so, what kinds of issues fuel the phenomenon of censorship?

- Political oppression as an historical phenomenon. Consider assigning students one historical example of political oppression (or allow them to select on their own with teacher approval). They could then compare and contrast their example with Taiwan’s “White Terror” era of martial law and Kun-lin Tsai’s struggle. Suggestions include the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Apartheid in South Africa, the Holocaust, and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Students could conduct research on the “White Terror” in Taiwan and one of the other historical examples and write an essay or present a slide presentation about their research to the class.

- Use interactive technology to learn about Taiwan’s economic and political development. Invite students to explore the Centering Taiwan in Global Asia curriculum resource website (https://centeringtaiwan.pitt.edu/), specifically its Modern Taiwan(https://centeringtaiwan.pitt.edu/taiwan/) and Modern Taipei (https://centeringtaiwan.pitt.edu/taipei/) pages, where they can learn about Taiwan’s post–White Terror political liberalization and the island’s economic ascendence starting in the latter half of the twentieth century and often referred to as the “Taiwan Miracle.” Lesson plans and document-based question activities are included on the website for K–12 classroom use.

Author: Catherine Fratto, Global Studies Center, University of Pittsburgh

2025