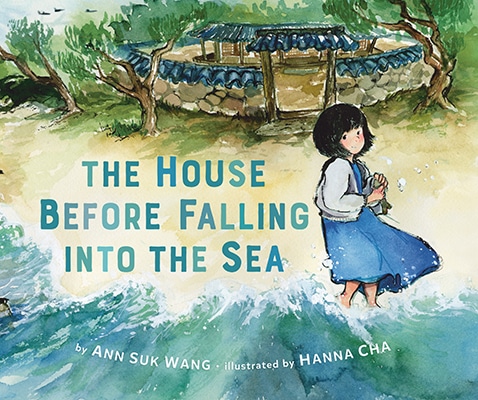

The House Before Falling into the Sea

(Dial Books)

- Fiction

- Set in Korea

Key words: Historical fiction, war, refugees, family

Every day, more and more people fleeing war in the north show up at Kyung Tak and her family’s house on the southeastern shore of Korea. With nowhere else to go, the Taks’ home is these migrants’ last chance of refuge “before falling into the sea,” and the household quickly becomes crowded, hot, and noisy. Then war sirens cry out over Kyung’s city too, and her family and their guests take shelter underground. When the sirens stop, Kyung is upset—she wishes everything could go back to the way it was before: before the sirens, before strangers started coming into their home. But after an important talk with her parents, her new friend Sunhee, and Sunhee’s father, Kyung realizes something important: We’re stronger when we have each other, and the kindness we show one another in the darkest of times is a gift we’ll never regret.

…all they had left weighed them down.

—The House Before Falling into the Sea (Page 1)

Appropriate for Grades: 3-12

Best for Grades: 5-10

Introduction to the Book

The House Before Falling into the Sea is a startlingly poignant picture book. Initially, it might appear to be written for very young readers, but it is so rich in its language and visual detail that it quickly becomes apparent how well-suited it is for use in the secondary classroom as well. The author and illustrator take full advantage of the medium, calling on their readers to read the text as poetry, consider the illustrations as fine art, and examine the relationship between the text and illustrations to find more meaning on each spread.

If teaching younger grades (Grades 3–5), a unit on the Korean War (1950–53) is not essential for the learning experience—the core themes will emerge with or without knowledge of the war. If teaching older grades and wishing to delve more specifically into the Korean War, this works better as a “bookend” experience, wherein the book is leveraged as an introduction to the war, and then reread at the close of the unit.

Teacher’s Note: The author’s note and illustrator’s note in the back matter are essential reading prior to using this book in the classroom.

Best Matched Curricular Unit Themes

- (Korean) War (History)

- Watercolor (Art)

- Prose Poetry (Language Arts)

- Generosity (Humanities)

Essential Questions (adapted from the back matter of the book)

- How do we define neighbor?

- Who are our neighbors?

- How do parents shape us?

- How can we show kindness to others?

Suggested Activities

Front Cover & Title. Explore and discuss any of the following:

- What the title refers to

- The composition of the cover illustration

- The relationship between the book title and the cover illustration

- The expression on the girl’s face

- What the girl is holding in her hand

- Who the girl might be

- What the three dark-blue things in the top left corner might be

Inside Covers (Front & Back). Look at the two inside cover illustrations before reading the story. Hypothesize on their relationship to one another, using clues from the images. After reading the book, reexamine them to confirm or rethink original hypotheses (Hint: look at them in relation to the final two-page spread of the story).

Language from Context. Throughout the story, the author includes Korean words and phrases (Umma, Appa, An neong ha se yo, and so on), many of which are translated in the back matter of the book. Before referring to the back of the book or searching the internet, have students attempt to use text and image context clues to guess at the meaning of as many of the words as they can.

Metaphors Everywhere. Go on a metaphor search, counting up how many metaphors the author uses to tell this story. (Hint: look for personification, too.) For a higher-level challenge, search out visual metaphors as well.

Stone Metaphor into Symbol. The most prevalent metaphor throughout is the stone (stone, pebble, rock). Create a list for each time this image appears and identify its metaphorical meaning. Using that list, draw conclusions as to what the stone ultimately means symbolically. This could be the basis of an intense debate and is therefore well-suited to a topic within a Socratic seminar.

Metaphor into Poetry. Select one metaphor (textual or visual) from the book and turn it into a poem.

Illustration into Narrative. Select one spread from the book and write a narrative for the page that is not descriptive of anything specific on the page (for example, do not write, “She crouches in her pink dress”). Instead, describe the emotions in the illustration, those feelings the brushstrokes on the page elicit (for example, “Sharp terror rushes through their taut braids.”). The teacher will gather these emotional descriptions and then distribute them at random to the students, who must then search for the page they think best matches the description they were given. They will then present to the class with an explanation of why they believe the description matches the illustration. The writer of the description reveals whether or not the presenter is correct with regard to which illustration they matched to it.

Suggested Discussion/Writing Prompts

Text-Illustration Integration. Select a page or a spread where the illustration and the text feel particularly interconnected, where each is made stronger and more impactful by the other. Share and discuss.

Poetry in Point of View. Write a poem from the point of view of different people in the story: Kyung, her mother, her father, Sunhee, Sunhee’s father, an unnamed guest.

Book Title as Metaphor. Write the title of the book at the top of the page. Then write an extended metaphor involving the idea of a “last house” and a “sea.” The extended metaphor could be related to either a contemporary or a historical issue; the metaphor could be wide-ranging and political (for example, the last house might stand for a major issue in society today) or emotional (for example, the sea could be the sorrow after loss).

Generosity. Define generosity (of spirit, of space, of possession, etc.). Debate the extent and limits to which generosity should be demonstrated as well as to whom it should be given. Include in the discussion whether or not different contexts demand different levels of generosity.

Author: Josh Foster, Educator and Learner

2025