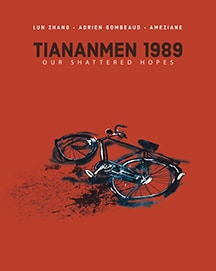

Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes

- Non-fiction

- Set in China

Keywords: graphic novel, politics, human rights, activism

Follow the story of China’s infamous June Fourth Incident — otherwise known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre — from the first-hand account of a young sociology teacher who witnessed it all.

Over 30 years ago, on April 15th 1989, the occupation of Tiananmen Square began. As tens of thousands of students and concerned Chinese citizens took to the streets demanding political reforms, the fate of China’s communist system was unknown. When reports of soldiers marching into Beijing to suppress the protests reverberated across Western airwaves, the world didn’t know what to expect.

Lun Zhang was just a young sociology teacher then, in charge of management and safety service for the protests. Now, in this powerful graphic novel, Zhang pairs with French journalist and Asia specialist Adrien Gombeaud, and artist Ameziane, to share his unvarnished memory of this crucial moment in world history for the first time.

Providing comprehensive coverage of the 1989 protests that ended in bloodshed and drew global scrutiny, Zhang includes context for these explosive events, sympathetically depicting a world of discontented, idealistic, activist Chinese youth rarely portrayed in Western media. Many voices and viewpoints are on display, from Western journalists to Chinese administrators.

Describing how the hope of a generation was shattered when authorities opened fire on protestors and bystanders, Tiananmen 1989 shows the way in which contemporary China shaped itself.

The 1989 Tiananmen Massacre was a pivotal moment in modern Chinese history—an eruption of youthful idealism and civil unrest that ultimately ended in tragedy. To understand this watershed moment, it is essential to place it within the broader context of China’s post-Mao transformation.

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, China was emerging from a decade of upheaval known as the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a chaotic campaign to enforce ideological purity that left millions displaced, persecuted, or dead. The Cultural Revolution had devastated China’s education system, economy, and intellectual class. In the wake of this turmoil, Chinese citizens craved stability, economic improvement, and a less dogmatic approach to governance.

Deng Xiaoping, a pragmatic leader who had survived political purges under Mao, gradually rose to power by 1978. Though he never held the formal title of head of state, Deng became the de facto leader of China. His vision was transformative: to modernize China through practical economic policies while keeping tight political control.

Deng’s “Four Modernizations” ushered in a period of rapid reform. He focused the government’s efforts on agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology. Collectivized farms were replaced by the Household Responsibility System, which gave farmers control over their land and profits. In cities, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) like Shenzhen attracted foreign investment, tested capitalist-style reforms, and transformed sleepy towns into booming industrial hubs. Universities reopened, and China’s long-neglected intellectuals and scientists returned to their labs and once again made valuable contributions to the nation’s future.

The results were dramatic: the economy grew rapidly, poverty declined, and millions joined the ranks of the new urban middle class. Yet these changes also brought growing social inequality, rampant corruption, and a rising tide of public frustration. Many Chinese, especially students and young professionals, began to ask: if we can reform the economy, why not the political system?

Throughout the 1980s, many intellectuals called for a “Fifth Modernization,” the advancement of democracy. Some of this momentum came from within the Communist Party itself. Hu Yaobang, a reform-minded party secretary, supported intellectual freedom and leniency toward democracy advocates. But his progressive stance angered party conservatives. In 1987, after student protests criticizing corruption and advocating for political reform, Hu was forced to resign.

The mood among the young remained defiant. Many university students were aware of democratic movements abroad and closely followed the reforms in the Soviet Union, where Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring) seemed to promise a freer, more democratic future. Students in China hoped their country might follow suit.

On April 15, 1989, Hu Yaobang died of a heart attack. Students in Beijing quickly organized public vigils in Tiananmen Square, ostensibly to mourn Hu, but also to signal their frustration with the stalled pace of reform. The square was a vast space steeped in revolutionary symbolism. The Great Hall of the People lay to its west, the Imperial Palace to the north, and Mao Zedong’s mausoleum in its center. The square quickly filled with tens of thousands of demonstrators.

Over the following weeks, the movement grew into a national event. Journalists, teachers, factory workers, and civil servants soon joined the students. The protesters were not a unified political force; they represented a broad spectrum of demands. Some wanted multi-party elections and press freedom. Others focused on ending official corruption and gaining fair educational and employment opportunities. Many simply demanded that the Communist Party live up to its own professed values.

By mid-May, the movement had captured the world’s attention. Foreign journalists had arrived to cover Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit to Beijing, the first by a Soviet leader since the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s. With global media in town, the Tiananmen protests quickly took center stage. Many journalists were captivated by the so-called Goddess of Democracy, a 33-foot-tall foam and papier-mâché statue created by students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which had a striking resemblance to the Statue of Liberty.

As momentum built, student leaders called for a formal dialogue with the government. When these requests went unanswered, some began a hunger strike, adding urgency and moral weight to their cause. Public support surged. In dozens of cities, sympathetic protests broke out. In Beijing, volunteers delivered food and water to the students, and even some members of the police and military supported the demonstrators.

Inside the Communist Party, a fierce debate raged. Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang’s successor and a fellow reformer, warned against the use of force and urged peaceful resolution. Premier Li Peng took a much harder line. By May 19, Deng Xiaoping had sided with Li and the hardliners, expelling Zhao from the party. Shortly thereafter, Zhao visited the square, tearfully asking the students to leave. “I have come too late,” he said. It was the last time he would be seen in public.

On May 20, the government declared martial law and mobilized tens of thousands of troops to encircle Beijing. For a time, ordinary citizens blocked the military’s progress, building barricades and pleading with soldiers. But Deng and the leadership were convinced that the protests threatened the Communist Party’s hold on power.

In the early morning hours of June 4, 1989, the military moved into Tiananmen Square. Tanks rolled over barricades. Troops opened fire on civilians. Protesters were beaten, arrested, shot, or crushed beneath armored vehicles. Foreign journalists captured harrowing footage that they then broadcast around the world.

Even today, the death toll is still uncertain. The Chinese government claims around 200–300 deaths. Independent estimates range from several hundred to as many as 3,000. Thousands were wounded or imprisoned. In the days that followed, thousands more were arrested, and a nationwide crackdown on dissent ensued.

Perhaps the most iconic image of the crackdown was that of “Tank Man”—an unidentified young man standing defiantly in front of a line of tanks. His fate remains unknown. His act of bravery is still one of the most recognizable symbols of nonviolent resistance in world history.

In the immediate aftermath, the Chinese government faced international condemnation. The U.S. and other nations imposed sanctions. Diplomatic relations cooled. Yet Deng Xiaoping remained committed to his long-term goal: economic modernization under single-party rule. In 1992, Deng doubled down on market reforms during his “Southern Tour,” ensuring that the party’s legitimacy would hinge on economic growth, not political openness.

Inside China, the government worked to erase the memory of Tiananmen. Teachers avoid the subject in schools, journalists do not mention it in the media, and censors remove all references to it online. Many young Chinese today have never heard of the Tiananmen Massacre.

Yet for those who remember, the lesson is stark: the Communist Party will not tolerate challenges to its authority. One such voice is Lun Zhang, a sociology professor who helped organize student safety during the protests. After fleeing China, he settled in France and later co-authored Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes, a graphic novel that offers a deeply personal account of the movement and its suppression. His story stands as both a warning and a call to remember.

Further works:

Lim, Louisa. The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Nathan, Andrew J., and Perry Link, eds. The Tiananmen Papers. New York: PublicAffairs, 2001.

Perry, Elizabeth J. and Mark Selden, eds. The Political Lives of Tiananmen: The Chinese Democracy Movement of 1989. Boulder: Westview Press, 1997.

Zhang, Lun, Adrien Gombeaud, and Ameziane. Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes. New York: IDW Publishing, 2021.

Zhao, Dingxin. The Power of Tiananmen: State-Society Relations and the 1989 Beijing Student Movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Author: David Kenley, PhD, modern China specialist

2025

Grade level

This firsthand account is appropriate for mature students in grades 11–12. Be aware that the book contains images of violence and carnage.The book could complement the study of the Tiananmen protests and crackdown in World History, AP Comparative Government, Current Affairs, or Global Studies classes.

Timelines

The events in the book are well organized, with dates for each major event, but this timeline would be useful when revisiting the events for discussion in class. Photos are included.

FrontLine PBS. “Timeline: What Led to the Tiananmen Square Massacre.” June 5, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/-timeline-tiananmen-square/

PBS, which produced the documentary Gate of Heavenly Peace for its Frontline series, also created a resource-rich website that provides a timeline listing major events in twentieth-century China from 1919 to 1988, followed by a separate list of the events of the spring of 1989. http://www.tsquare.tv/chronology/

Primary Source Documents

Activities with documents

Each of the documents below has a direct connection to an event in the book; I’ve noted the page number of the event to which each document is connected.

After reading the document, ask students to complete the following activities:

- Have the students explain what the document adds to their understanding of the event as described by Lun Zhang. Identify any questions the document raises about the author’s description of the event. What does his firsthand account contribute to understanding the document?

- Have students locate a news account of the event related to the document from 1989. Compare the news coverage of the event with what is described in the primary source and what they learned from the book. Explain either how the news article accurately explains the event or how it misunderstood or misrepresented the event.

Democracy Wall

Lun Zhang explains that he saw the student activities in 1989 as an extension of the Democracy Wall movement in 1978–79, when people posted “big-character posters” criticizing the Cultural Revolution and calling for greater freedoms (p. 14).

Big-character posters are handwritten in large Chinese characters so that their messages can be easily read when posted in public places. The key document from that period is Wei Jingsheng’s call for democracy as a fifth modernization, in addition to Deng Xiaoping’s Four Modernizations: agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology. Wei’s writing and activities landed him in prison for fifteen years.

The document contains an introduction for context and a short excerpt from the essay with discussion questions followed by the full text of the essay.

Jingsheng, Wei. “The Fifth Modernization: Democracy.” Asia for Educators: Columbia University.https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/wei_jingsheng_fifth_modernization.pdf

Seven student demands to the government

On the day of Hu Yaobang’s funeral a group of student representatives presented seven demands to the government. They used the traditional gesture of “kneeling, hands raised heavenward, brandishing their letters of grievance” (p. 34). The following is from an article published on the thirtieth anniversary of June 4. The article contains the students’ seven demands, excerpts from several additional documents, and some photographs.

At the state funeral for Hu Yaobang at Tiananmen Square, four students broke through the security cordon. They knelt on the steps of the Great Hall of the People, asking to speak with Premier Li Peng and present him with seven demands. The premier refused to grant them an audience. Here are the seven demands:

- Affirm Hu Yaobang’s views on democracy and freedom as correct.

- Admit that the campaigns against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalization had been wrong.

- Publish information on the income of state leaders and their family members.

- Allow privately run newspapers and stop press censorship.

- Increase funding for education and raise intellectuals’ pay.

- End restrictions on demonstrations in Beijing.

- Provide objective coverage of students in official media.

Cilker, Noel C. “Primary Source: Protest, Tragedy, and Hope at Tiananmen Square.” June 4, 2019. https://noelccilker.medium.com/primary-source-protest-tragedy-and-hope-at-tiananmen-square-5ef78b0280e6

People’s Daily editorial

On April 26, 1989, the Party published an editorial in The People’s Daily warning of the chaos caused by the demonstrators and describing what actions must be taken to return order to the capital. Lun Zhang states, “It was the editorial that set our movement down a path of no return” (p. 37). The People’s Daily is the official mouthpiece of the Party. The editorial characterized the students’ movement as dangerous and suggested that people with ulterior motives were “taking advantage of the students’ feelings of grief for Hu Yaobang.”

People’s Daily. “It Is Necessary to Take a Clear-cut Stand Against Disturbances.” April 26, 1989. http://www.tsquare.tv/chronology/April26ed.html

Student hunger strike

A turning point in the movement was the students’ decision to stage a hunger strike (Act III, p. 51). In their declaration, the students made a plea to fellow citizens to not let their suffering be in vain. The document is presented here with a short introduction for context and the full text with discussion questions.

Columbia University. “The May 13 Hunger Strike Declaration.” Asia for Educators. May 13, 1989. https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/china/tiananmen_hunger_strike.pdf

Martial law declared

On May 19, Li Peng delivered a speech on TV announcing that martial law would be imposed starting May 20 (Act IV, p. 67).

“Li Peng Delivers Important Speech on Behalf of Party Central Committee and State Council.” http://www.tsquare.tv/chronology/MartialLaw.html

Interview with Chai Ling

Chai Ling was the “Commander-in-Chief of Defend Tiananmen Square Headquarters” (p. 74). In this interview, she describes the situation a few days before the army arrives at Tiananmen Square. She is one of the few student leaders who succeeded in escaping from China after June 4.

Ling, Chai. “Interview at Tiananmen Square.” Asia for Educators: Columbia University.

https://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1950_chailing.htm

The official government account

The presence of Western reporters and media meant that the world outside of China witnessed the events of the student protests and June 4 in real time.

Immediately afterward, the Party began a campaign of revisionism and censorship surrounding the events. In a book published by Beijing Publishing House, the Party told its version of the story in both Chinese and English. The book is richly illustrated with pictures that emphasize the squalor in Tiananmen Square during the hunger strike, the presence of “outside agitators,” several episodes of violence against soldiers, and the “restoration of order” after the “appalling riot.” The following is the Introduction to the book.

“The Truth about the Beijing Turmoil.” Edited by the Editorial Board of The Truth about the Beijing Turmoil. Beijing Publishing House, 1990. http://www.tsquare.tv/themes/truthturm.html

Tiananmen Mothers

Many of those killed the night of June 4 were never identified by the government, and their families never received official confirmation of their deaths. Following the death of her son Jiang Jielian, Ding Zilin began to seek out the parents and relatives whose loved ones did not return home after June 4. She established a group she called Tiananmen Mothers, and along with her husband Jiang Peikun, she sought to uncover the truth about those who died and especially those who never returned.

For her activism, she lost her job as a university professor and was held under house arrest during the 1995 Women’s Conference in Beijing. The link below is to the Human Rights in China website, where thirty-one of the testimonies she collected can be viewed, including her own.

“A collection of 31 first-person accounts by survivors of the June Fourth crackdown and family members of those killed. These accounts were collected by the Tiananmen Mothers and issued by HRIC [Human Rights in China] in Chinese and English translation in 1999 to commemorate the victims on the 10th anniversary of the crackdown. Together, these accounts provide a picture of what happened on the night of June 3–4, 1989, and the days that followed, and are enduring testimonies supporting the demands of survivors and the families of the victims for truth, accountability, and compensation.”

Testimony of Ding Zilin, founder of Tiananmen Mothers

“After the June Fourth Massacre, Jiang Jielian was the only casualty of high-school age whose death was acknowledged in internal bulletins by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) authorities. Now it is known, however, that there were at least nine high-school students killed in the massacre. On September 11, 1989, on the hundredth day after his murder, we took his ashes home and put them where his bed had been before his death. On the front of the box where the ashes are kept, his father carved the following inscription for our beloved son:

In these short 17 years

You lived like a real man

Your humanitarian nobility and integrity

Will be kept in the undying memory of history.

Your forever loving Father and Mother.”

https://www.hrichina.org/en/testimonies-survivors-and-families-victims-june-fourth-crackdown

Activities Using Images

Images have a tremendous power to shape our understanding or misunderstanding of events.

“Tank Man”

Brown University’s Watson Institute for International Studies publishes the award-winning Choices curriculum units. The following activity uses the iconic image of the “Tank Man,” a photograph taken by Associated Press journalist Jeff Widener. The activity focuses on the topic of censorship vs. the freedom of information.

Watson Institute for International Studies. “Looking at the Tank Man: The Twentieth Anniversary of Tiananmen.” A Supplement to “China on the World Stage: Weighing the U.S. Response.” Brown University Choices Program. https://www.choices.edu/teaching-news-lesson/looking-tank-man-20th-anniversary-tiananmen/

Getting beyond “Tank Man”

There’s no argument that “Tank Man” is the most iconic image to emerge from the Tiananmen protests, but an international corps of journalists documented the movement—from the early tribute gatherings for Hu Yaobang through the dawn of June 4, when the extent of the military action became clear. Many of their images vividly capture the spirit of the protesters and the tragedy of the crackdown.

Have students choose an image depicting any episode from the book and make an argument as to why the image they have chosen is important to understanding the events Lun Zhang and the other protesters experienced. Students can do a Google search using Tiananmen Square protest photos or check out one of the following sites to find a range of pictures.

Jeff Widener’s photographs

Almond, Kyle. “The Story Behind the Iconic ‘Tank Man’ Photo.” CNN. June 5, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/05/world/tiananmen-square-tank-man-cnnphotos/

A selection of rare black and white photos

NPR staff. “30 Years after the Tiananmen Protests, ‘The Fight is Still Going On.’” NPR. May 31, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2019/05/31/727846940/30-years-after-tiananmen-protests-the-fight-is-still-going-on-for-china

Sherin, Kelly. “32 Photos Show the Hope and Despair of Tiananmen Square.” Esquire, June 4, 2021. https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/g36621881/tiananmen-square-massacre-photos/

Looking Back: Reflecting on June 4

“Journalism is the first rough draft of history.”

—attributed to Philip L. Graham, president of the Washington Post

“The living should really shut their mouths and listen to the graves speak.”

—Liu Xiaobo

Those who experienced the events of 1989 and survived continue to reflect on what happened with a combination of sorrow, survivor’s guilt, and resolve. Some still second-guess decisions they made, especially some of the leaders. Below are reflections by student leader Wang Dan, Nobel Peace Prize–winning democracy activist Liu Xiaobo, and a series of video interviews with participants and witnesses (from the documentary The Gate of Heavenly Peace).

Students then and now

Read the op-ed by Wang Dan and the article by Sharon LaFraniere. Compare Wang’s view of young Chinese with LaFraniere’s reporting. Ask the students to explain why they think there is a difference between Wang’s view of them and what LaFraniere reports on what they say about themselves.

Wang Dan. “What I Learned Leading the Tiananmen Protests.” New York Times. June 1, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/01/opinion/sunday/tiananmen-protests-china-wang-dan.html?searchResultPosition=7.

Wang Dan was one of the student leaders who fled Beijing but was arrested and sentenced to four years in prison. After his release, he continued his calls for government reform and was once again arrested and sentenced to eleven years in prison. He was released due to health problems and lives in the United States. This op-ed was published to acknowledge the thirtieth anniversary of June 4.

“Young people in China today, nearly all of whom grow up in one-child families, are more pragmatic than we were in the 1980s. And despite the government’s brainwashing, they know how to use technology and obtain information from the outside. They understand more about the West than we did. Unlike students of my generation who held false hopes for the party, members of today’s younger generation are more cynical and realistic. Once opportunities arise, they’ll rise up as we did 30 years ago.”

LaFraniere, Sharon. “Tiananmen Now Seems Distant to China’s Students.” New York Times. May 21, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/22/world/asia/22tiananmen.html?pagewanted=1

“And if a student today proposed a pro-democracy protest?”

“People would think he was insane,” said one Peking University history major in a recent interview. “You know where the line is drawn. You can think, maybe talk, about the events of 1989. You just cannot do something that will have any public influence. Everybody knows that.”

“Most students also appear to accept it. For 20 years, China’s government has made it abundantly clear that students and professors should stick to the books and stay out of the streets. Students today describe 1989 as almost a historical blip, a moment too extreme and traumatic ever to repeat.”

Memory and resolve

Liu Xiaobo was a pro-democracy activist who served prison terms for his actions during the Tiananmen protests and, later, for participating in the writing of Charter 08, a manifesto calling for democratic reform. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 but was in prison and prevented from attending the ceremony.

He wrote a series of poems commemorating the Tiananmen Massacre entitled June Fourth Elegies: Poems.

“June Fourth in My Body” by Liu Xiaobo (2009)

https://www.cnn.com/2014/06/03/asia/gallery/liu-xiaobo-poem/index.html

Here is a short excerpt:

The day

seems more and more distant

and yet for me it

remains a needle inside my body…

This needle

that has stayed for so long round the heart’s periphery

is determined to plunge inside

and bring an end to all guilt

but then just before acting

it hesitates

not daring to move forward

Nobel Peace Prize lecture by Liu Xiaobo in which he makes his case for democracy. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2010/xiaobo/lecture/

Gate of Heavenly Peace (PBS)

For six years following the events of June 4, a team of international scholars worked with filmmakers to create the documentary Gate of Heavenly Peace, which aired as part of the Frontline series. The documentary includes footage from 1989 along with interviews from participants collected over the six years that followed. The film is one of the richest records of this chapter in Chinese history because it contains both video recorded at the time and interviews in which participants reflect on how they viewed these events later.

Home page: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/gate/

Key excerpts from the film: http://www.tsquare.tv/film/gateExcerpts.php

Chai Ling hoping that Chinese government will kill the Tiananmen students: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5__ESiklA1A

Additional Resources and Reading

Liu, Binyan. “Tell the World”: What Happened in China and Why,” translated by Henry L. Epstein. New York: Pantheon Books, 1989.

Brook, Timothy. Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Salisbury, Harrison E. Tiananmen Diary: Thirteen Days in June. Boston: Little, Brown, 1989.

Shen, Tong, and Marianne Yen. Almost a Revolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Turnley, David and Peter. Beijing Spring. Stewart Tabori & Chang, 1989.

Human Rights in China website

“Human Rights in China (HRIC) is a Chinese non-governmental organization (NGO) founded in March 1989 by overseas Chinese students and scientists. We actively engage in case and policy advocacy, media and press work, and capacity building. Through our original publications and extensive translation work, HRIC provides bridges and uncensored platforms for diverse Chinese voices. Our activities promote fundamental rights and freedoms and provide solidarity for rights defenders and their families by supporting citizens’ efforts to effectively communicate, as well as organize and participate in rights defense activities.”

https://www.hrichina.org/en/june-fourth-overview

Author: Cindy McNulty, NCTA consultant and retired high school history teacher

2025