Tsunami Girl

- Fiction

- Set in Japan and England

Keywords: contemporary, coming-of-age, earthquake, tsunami, survival

Fifteen-year-old Yuki is struggling at school with her confidence, and goes to Japan to stay with her grandfather, a well-known manga artist and to whom she is very close. But during her visit, a calamitous event occurs – the East Coast Earthquake and Tsunami – and her beloved Grandpa is lost.

Yuki and her friend Taka must make sense of the terrible situation and come to terms with the loss of their life as they knew it – and see that through renewal and with resilience, they can emerge from this tragedy with optimism for the future.

Interwoven with Japanese folk tales, modern-day ghost stories, and the creation of her very own vibrant manga hero, Yuki finds the courage to overcome extraordinary odds, and take her first steps into the world that lies beyond catastrophe.

Told through both prose and manga, with powerful, emotional manga from acclaimed Japanese artist, Chie Kutsuwada, this story for young adults will touch the heart of readers of all ages.

Tsunami Girl is published in two formats—manga and prose—bound into a single volume. The story is set during the Tōhoku (pronounced: TOE-HO-ku) earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, known in Japan as the Great East Japan Earthquake. The protagonist, Yūki, is a 15-year-old girl who was swept out to sea in the tsunami. After drifting for hours on a raft, she is washed up on shore and miraculously survives.

Yūki lives in England with her parents. She was visiting her grandfather in Fukushima prefecture when the tsunami struck. After recovering from her ordeal in England, she returns to Japan to search for her grandfather, who is presumed lost at sea. She revisits her hometown of Minamisōma, near the Fukushima nuclear plant.

The earthquake occurred 72 kilometers (45 miles) off the Pacific coast of Miyagi prefecture at a depth of 24 kilometers (15 miles). Almost the entire main island of Honshu shook violently for several minutes, causing serious damage to property. Shaking destroyed some 123,000 houses and damaged a million more. A tsunami followed approximately 30 minutes after the earthquake, devastating the coastal towns of Iwate (pronounced: e-WAH-tay) and Fukushima prefectures. More than 22,000 lost their lives. Many were washed out to sea.

The tsunami crippled the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, located on the coast 175 kilometers (109 miles) southwest of the earthquake’s epicenter. Before the plant could be shut down, the electrical supply to the cooling system was damaged, prompting the backup generator to come on. The tsunami that hit the plant was 15 meters (50 feet) high, easily topping the seawall and flooding the generator room, which made the first backup generator inoperable. The second backup generator was also lost in the flood. Without a continuous supply of cooling water, the nuclear generators were in serious danger of a meltdown. Initially, helicopters were used to douse the plant with water, and then fire trucks were deployed to hose down the nuclear core. None of these efforts were enough to stop the meltdown. The core overheated and melted into the reactor base, causing radiation damage worse than the levels after the 1986 accident at Chernobyl in Russia.

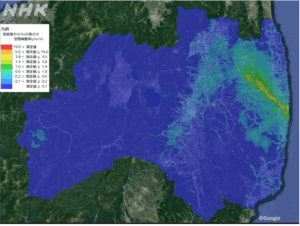

The radioactive steam that was released traveled miles from the plant, blown to the northwest by the wind. To avoid exposure, residents within 20 kilometers (12 miles) of the plant were advised to evacuate immediately to avoid exposure to the radiation from the failed nuclear plant. As a result, 164,000 residents in a 20-kilometer radius evacuated from the danger zone, leaving everything—homes, stores, offices, and farm animals.

By the end of 2023, some parts of the evacuation zone were declared safe, and people returned, but more than 26,000 remain displaced for a variety of reasons. At the end of 2023, a sliver of an area extending northwest from the nuclear power plant (337 km2 or 130 m2) was declared a “Difficult-to-return” zone, where residence is limited. The radiation levels in Fukushima prefecture have dropped to less than 20 mSv, but in some areas, radiation still measures up to 19 mSv, and such areas are designated “Difficult-to-return.” As a reference, an exposure of 20 mSv a year is the guideline for any radiation worker; this is considered a safe level. (A CT scan can give 10 mSv of radiation.)

The shaking of the earthquake was felt in all parts of Japan, including in some parts of the southernmost island of Kyushu. The earthquake registered at a magnitude ofn Mw9.1, making it the largest in Japan’s history. The Japanese earthquake intensity scale (shindo) that measures the intensity of shaking in a particular location was 7 north of Sendai. At Minamisōma, the setting for this story, the shindo was 6+. The shindo intensity scale goes from 0 to 7, with 0 being not sensed and 7 being the most intense.

As one can imagine, the human suffering caused by the earthquake was unimaginable; even today, the scale of devastation is still difficult to comprehend. Mental illness arising from the disaster has been reported, including PTSD. After the 2011 earthquake, a new government agency (called the Reconstruction Agency) was established to manage and coordinate the reconstruction.

Mental illness issues are often touched on in the book. In particular, the main character suffers from social anxiety and, for that reason, is homeschooled. Historically, Japanese people regarded mental illness, except for severe cases, as a sign of personal weakness and lack of fortitude. When mentally ill people behaved oddly, they were labeled kichigai (crazy) or seishin byō (mentally ill; the word carries a severe connotation) and could be committed to home confinement or mental institutions.

Since the late twentieth century, attitudes and policies have shifted. Instead of committing patients to mental institutions, mental health care is now provided to patients living in the community. This is in tune with similar models in the West. Accordingly, the legal framework, methods of treating mental health, and media reporting have changed. People have generally become more accepting of mental illness and more attuned to calling out discriminatory practices.

With the introduction of a new law in 2020, any physical violence or abusive language in schools must be reported to the authorities. Three-quarters of primary and secondary schools have access to school psychologists, who help with mental illness as well as bullying, truancy, and discrimination connected to personality disorders. Mental illness cases are treated using cognitive and behavioral therapies as well as drug intervention, following the diagnostic guidelines in ICD-10. Despite the increasing awareness, people are sometimes reluctant to seek help from psychologists or psychiatrists due to the traditional stigma still attached to seeking help. A chronic lack of mental health care providers is also a factor.

Truancy is on the rise. Homeschooling is not legal in Japan, so when truancy occurs, school psychologists are brought in to help remedy the situation. More than 2 percent of schoolchildren often miss school. Another related problem is hikikomori (social withdrawal) or the avoidance of social interaction, including long periods of absence from school. This has become a more visible social problem in recent years. The total number of hikikomori is estimated to be 1.46 million people between 15 and 64 years of age.

Children of mixed heritage, of which the protagonist is one, are called hāfu. Yūki often experiences discrimination and bullying in Japan. The term hāfu applies mostly to children born to Japanese and Western (white) parents.

The protagonist lives in England and some of the story takes place there. The author and the publisher are British. So, it is not surprising that British words—jumper for sweater, for example—as well as colloquialisms (bloke) and idioms (pack it in)—appear in the text. British humor (satire and absurdity) is used.

The author mentions the supernatural and ghosts, such as funayūrei and zashiki warashi, as well as myths and folklore. Passing reference to catfish is made, as the catfish is associated with earthquakes in Japanese folklore.

Japanese words and expressions appear throughout the book. Some of these words are listed in the Japanese glossary, but others are not (bon, gekiga, daijōbu, and doki doki, among others). The expression nemimi ni mizu means to be taken by surprise, whereas the text gives only the literal translation of “cold water in a sleeping ear.” We learn that schoolchildren are taught a mnemonic to remember the correct way to behave while evacuating in a major earthquake or fire: okashimo. Each syllable in okashimo stands for a rule: o for osanai (do not push), ka for kakenai (do not run), shi for shaberanai (do not talk), and mo for modoranai (do not return). The author makes a mistake with ka (do not run), writing incorrectly that it means do not “shout.”

Despite these issues, Tsunami Girl offers important insights into how the Japanese have come to terms with the tragedy of 3.11—shorthand in Japan for the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which occurred on March 11, 2011.

Author: Hiroshi Nara, Professor Emeritus, University of Pittsburgh

2025